Extracts from the official summary

The key details of this unfortunate incident are provided in the following extracts from the official Board of Trade report produced by Lieutenant-Colonel J.W. Pringle:

I have the honour to report for the information of the Board of Trade, in accordance with the Order of the 21st January, the result of my inquiry into the cause of the derailment of a passenger train, which occurred about 3.58 pm., on the 19th January, between Little Salkeld and Lazonby, on the Midland Railway.

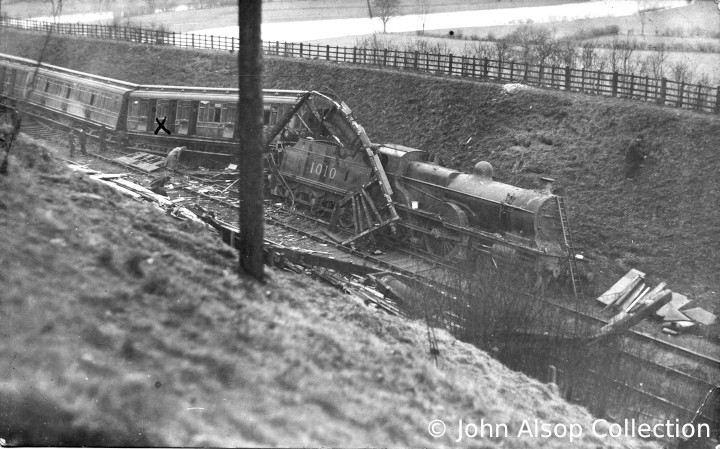

In this case, when the 1.45 p.m. down express from Leeds to Carlisle (8.50 a.m. St. Pancras to Glasgow) was travelling between the named stations, it ran into a quantity of sand and earth which had fallen from the side of the cutting. The whole of the train with the exception of the last bogie-truck, left the rails. The engine, after derailment, travelled a distance of about 180 yards over the ballast. The first and second vehicles shot off down the road, and were broken up, but the remaining coaches kept their alignment behind the engine, and suffered less damage.

I regret to report that six passengers were killed, and that one subsequently died from the effects. In addition, 37 passengers, including two officers and four soldiers, suffered more or less severe injury, or shock effect. Nine also of the Midland Railway Company's servants, four of whom were travelling as passengers, received minor injuries.

The express comprised a Class 4 compound engine, No. 1010 (type 4-4-0), with 6-wheeled tender, and ... eleven vehicles.

... About 156 yards of the down track were destroyed, and 56 yards of the up track damaged.

... The evidence - which has not been printed - does not conflict on any material fact, and points to the conclusion that this serious accident was caused by circumstances which could not reasonably have been foreseen, or prevented.

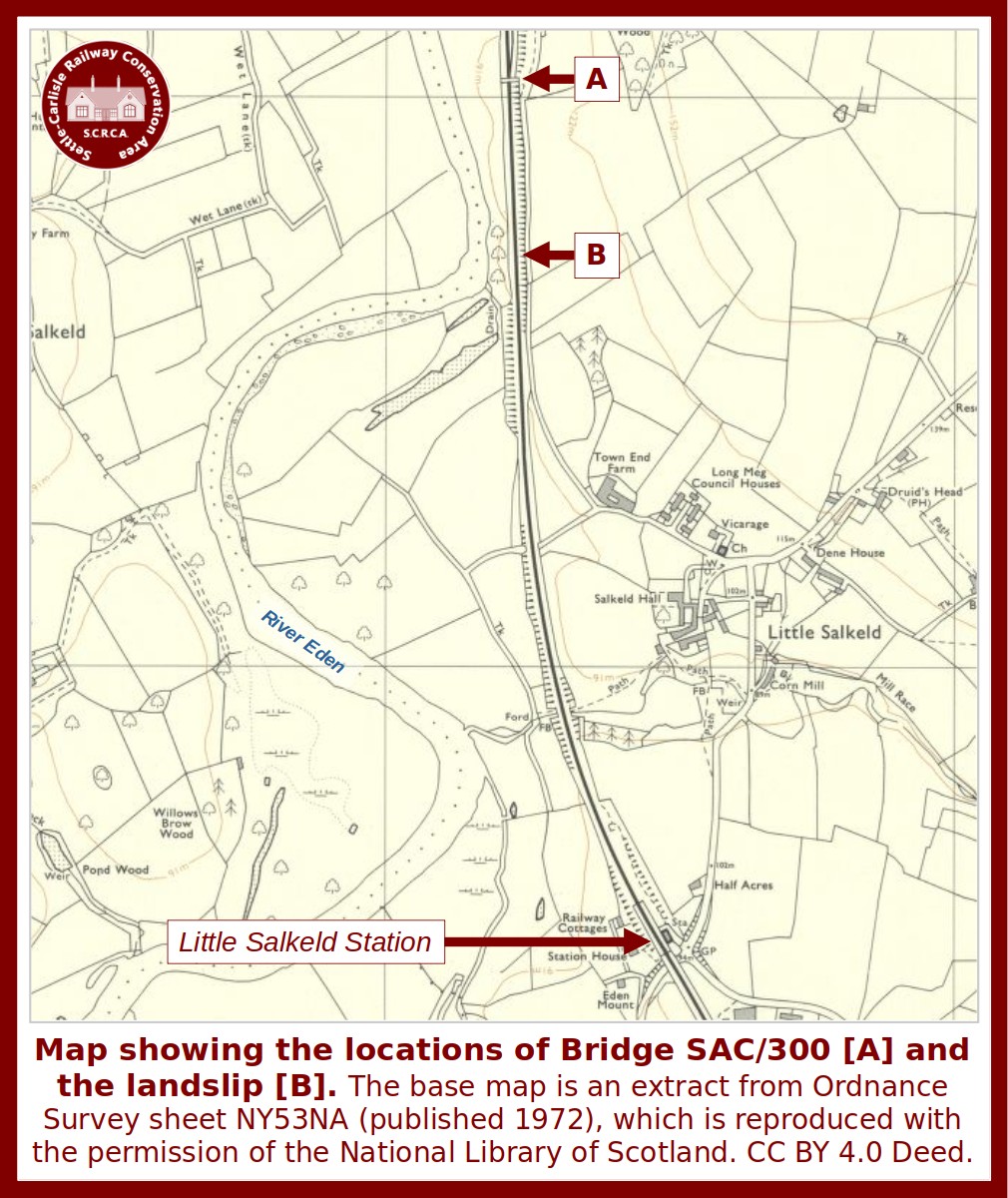

... The slip was at mile 290, 38 chains*.

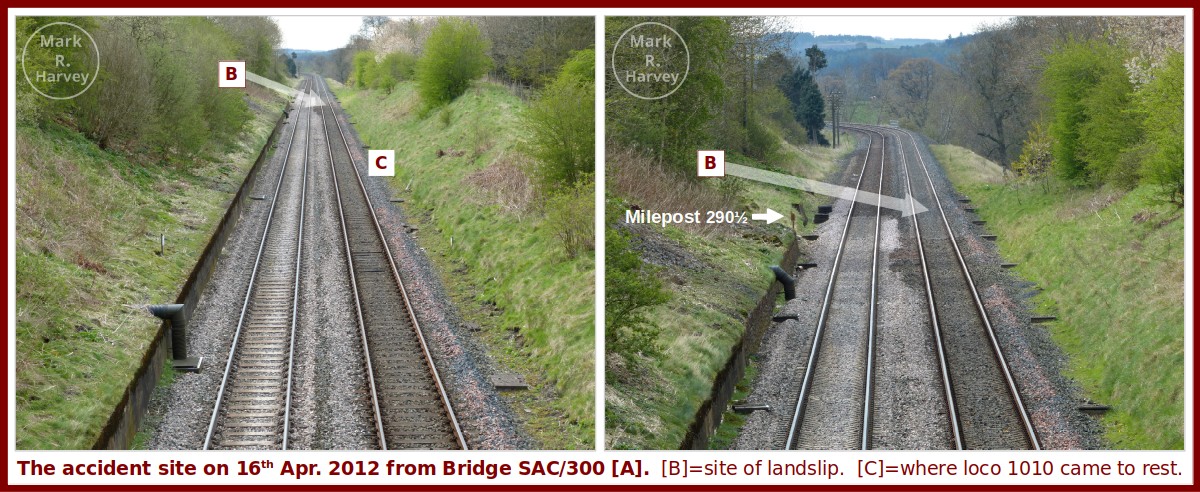

* There are 80 chains in a (UK) statute mile and 22 yards (66 feet) in a chain, so the landslip was 2 chains (44 yards or 132 feet) south of Milepost 290½. The rear of the milepost is clearly visible (bottom centre) in image A3. It is too small to see clearly in Image A2, but it is located between the two rail-cranes.

According to the report, the debris from the landslide was extremely "fluid" and it covered both lines of track for a width of "from 80 to 100 feet" and to a depth of "about 2½ feet above the rails". The light-coloured patches visible beside the recovery train in Image A2 are probably what remained of this debris after the 'up' line (nearest to the camera) had been cleared sufficiently to allow rail vehicles to access the site.

Image Gallery A: 1918

Four photographs showing the aftermath of the accident, courtesy of John Alsop:

Image Gallery B: 2012

Image B1

The two photographs were taken on 16th April 2012 from Bridge SAC/300, which is labelled [A] on the map (see Figure 1). In the second photo, Milepost 290½ is indicated by an arrow & label. The site of the landslip has been labelled with [B], while [C] indicates where loco 1010 came to rest.

Partial transcript of a news report from the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, Monday 21 January 1918

SCOTCH EXPRESS WRECKED NEAR CARLISLE.

DISASTER CAUSED BY A LANDSLIDE.

SIX PASSENGERS KILLED.

(FROM OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT.)

Carlisle, Sunday Night.

A remarkable railway disaster, involving the death of six passengers and injuries more or less severe to at least eight others, occurred yesterday afternoon on the Midland system in the Eden Valley, some 16 miles south of Carlisle. The Scotch express running between St. Pancras and St. Enoch's, Glasgow, became derailed through a landslip from the side of the embankment, and after ploughing up the permanent way for a distance a hundred yards, turned on its side and became a total wreck, two of the leading coaches being telescoped in the process. Bad as the accident was, however, the only wonder is that the death-roll is not much greater than it is. It seems somewhat curious that the biggest smashes the Midland Company have had occurred in this northern part of their system. ...

The point where the accident occurred lies between the small wayside stations of Little Salkeld and Lazonby, where the River Eden winds its way through the valley, and runs alongside the railway line. Hereabouts there are a number of cuttings, and it was in one of these, know as Long Meg Deep cutting because of some local Druidical associations, that yesterday's express came to grief. The train in question was the 8.50 a.m out of St. Pancras, reaching Leeds at 1.45 p.m. and due to arrive at Carlisle at 4.18. It was composed of eleven corridor carriages, and was drawn by one of the company's latest type of locomotives. The express was fairly well filled when it left London, and the last stop was Skipton. After climbing up the hills towards the Yorkshire border, where it had the assistance of a second engine, it then ran for some miles down the incline into the Eden valley with steam off. In common with other parts of the country Cumberland had experienced a rapid and sudden thaw following a series of heavy snowstorms, and for some days the melting snow had rendered the low-lying lands very soft, and this has, undoubtedly, had a great deal to do with the disaster.

Be this as it may, what happened is now clear enough. Just as the express reached this particular cutting the clayey soil of the embankment gave way, yielding, perhaps, to the vibration caused by the fast approaching express, and flooded the railway track below. The driver of the train, travelling, perhaps, at the rate of between 40 to 50 miles an hour, then saw the landslide, but in less time than it takes to tell his engine was ploughing through mud and stones, and throwing the debris many yards high. He immediately applied the brakes, but in a second the engine was off the line, wobbling about, as he put it to me to-day. "as if it were in a rough sea." A moment later the great locomotive, its intricate wheels and machinery clogged with stones and dirt, and itself covered with mud, caught the side of the opposite embankment and, rolling over on its side, came to a standstill. The two next coaches to it, also off the line, crashed into the tender, and were quickly reduced to matchwood, much of the steel of the bogeys mounting high above the tender, and forming, with the fantastically wrecked woodwork of the carriages, a sort of bridge across both sets metals. The other carriages of the train also jumped the metals, and, in more or less damaged condition, rolled into the side of the embankment.

What happened to the passengers may be best told in the words one of them, Lieut. A. F. Thompson, of the Royal Flying Corps, a son of Mr. A. W. Thompson, jeweller, of Scarborough, whom I saw to-day happily little the worse for his extraordinary adventure.

I was sitting in a compartment in the middle of the train with four others, he said, when I felt one big bump, as if the brakes had been sharply applied, and we were all thrown from our seats. Then we had a still bigger bump. I tried to get to the window to see what had happened, when I was caught on the head with some woodwork and knocked to the far side of the carriage. All of sudden the carriage tilted over at a frightful angle, and an officer friend who was travelling with me scrambled out of the window. All the time steam was coming from the engine in a most alarming way. Going to the front part of the train we found the wreckage of the first two coaches stretched high across the line. People were trying to get out of the train, but there was singularly little panic. Near the smashed woodwork behind the engine some women and children were lying, and it looked as if they were past human aid. All the luggage was in the front van, and it was underneath the wreckage. One poor fellow was pinned by ironwork on his chest, a soldier was pinned by the ankle and could not move, a little boy about five years of age presented a very pitiful sight .... Axes procured from the rear of the train were quickly brought into use by railway workers and uninjured passengers. Unfortunately there was not a single doctor on the train, but there were a number of V.A.D. nurses, and they worked right manfully in succouring the injured and applying restoratives to them. Two of the women dining-car attendants also helped the noble work. It is a curious thing that only a minute before the accident happened one of the passengers made a remark about the Aisgill disaster, and no sooner had he spoken than this thing happened.

Lieut. Thompson pointed out to me what, indeed, was patent to anybody who visited the scene - that there is little doubt that had the embankment given way a hundred yards further south the train would have overturned into the River Eden, which was in flood, close by, and that if, on the other hand, it had occurred a hundred yards nearer Carlisle the train would have crashed into a stone bridge which carries the road over the railway. The results in either case would have been appalling.

Further reading

A copy of the official Board of Trade report produced by Lieutenant-Colonel J.W. Pringle on 9th February, 1918 can be downloaded from the Railways Archive via the following link / URL:

https://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/docsummary.php?docID=310

Acknowledgements

This snippet was researched and created by Mark R. Harvey.

The extracts from the official Board of Trade report and the contemporary newspaper account were transcribed by Mark R. Harvey from digital images of the original sources made available by the Railways Archive (see above) and the British Newspaper Archive (https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/).

Images have been obtained from various sources and they are acknowledged individually via watermarks and / or notes in the related captions.