Spoil tips are clearly defined areas of raised ground formed by the systematic tipping of 'spoil' (i.e. waste rock and / or earth) extracted during the process of excavating cuttings and constructing tunnels.

The process outlined below relates to the construction of a tunnel via an access shaft. The process for excavating cuttings and for driving ground-level tunnel headings would have been similar, albeit without the complications caused by the need to lift waste material to the surface via an access shaft. In terms of the workforce, miners typically worked underground, whereas quarrymen were often employed in cuttings. Labourers were employed in all cases.

- Miners working from the tunnel floor or platforms on a 'travelling stage' used rock drills, explosives, picks, crowbars, shovels and muscle power to remove rock and spoil from each working face. The following excerpt from the June 22nd, 1872 edition of the Lancaster Guardian provides us with an insight into this hard and dangerous process. The extract comes from a detailed account of a visit by the writer to Black Moss / Rise Hill Tunnel: "Being curious to see what was going on in the tunnel , I descended with two of the men number one shaft. The gloom in the rocky excavation, the hammering of drills, the voices of the men and the dim lights of candles gave to the murky scene a novelty that will long be remembered. The tunnel needs no lining with bricks on account of the tenacity of the rock, pieces of which weighted more like iron than stone. Some idea may be formed of the hardness of the rock when it is stated that thirty-five drills have been blunted with 18 inch boring. The atmosphere is so close in the tunnel that the men have to strip to their flannels. In blasting the rock it requires more than ordinary care, as sometimes pieces of 15cwt. fly to the distance of 20 yards."

- Labourers used wheelbarrows or temporary tramways to move waste material from the working faces to the base of the access shaft. In his contemporary account "The Midland railway: its rise and progress. A narrative of modern enterprise" (Published by Strahan & Co London in 1876), F.S. Williams refers to "uncouth looking waggons standing on the rails or moving to and fro" within the underground workings for Rise Hill Tunnel.

-

Figure 1: Illustration of a typical 'Horse Gin' from F. S. Williams: 'Our Iron Roads' (2nd Edition, 1883, page 153).

To view a larger version, click / tap the thumbnail.At the top of the shaft, the waste would have been transferred into wheelbarrows or, more likely, tramway tipper wagons. The shaft-head equipment would almost certainly have included a rotating jib to make the transfer of material as easy as possible.

- Labourers would then have pushed the wheelbarrows or tramway tipper wagons along temporary wooden barrow-runs or metal tramway tracks to a tipping point. (It is possible that horses may have been used to pull tramway wagons full of spoil to the tipping point. However, most of the tipping runs associated with the construction of the Settle-Carlisle Railway are very narrow, possibly too narrow for a horse to stand-aside or turn safely at the tipping point.)

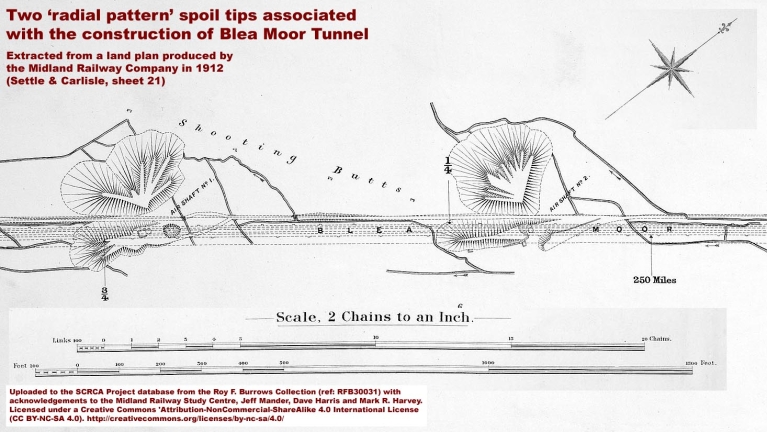

- It is clear from observations on the ground at various locations within the SCRCA that, once the spoil had been raised to the surface, the contractors worked with gravity (rather than against it) wherever possible. In other words, the barow runs / tipping tramways were laid on ground that had been either levelled, or graded with a slight downward slope. In addition, the tipping points always faced towards lower ground - as can be seen in scrca-image-2497802012-03-24mrhstbmt-shaft-1-spoil-wcontext-sw (a photograph showing the three spoil tips on the southern flank of Blea Moor).

- Each wheelbarrow or tramway tipper wagon was pushed to the edge of the current tipping face, where the waste material would be tipped-out in a 270 degree spread, eventually forming a slight bulge in the tipping point. As with most aspects of railway construction during the Victorian era, this tipping process could be very dangerous, as evidenced by the contemporary account from the February 15th, 1873 edition of the Lancaster Guardian.

- Subsequent loads would gradually extend this bulge into a finger-shaped ridge or tipping line. As the length of the tipping line grew, the barrow run or tramway track would have been extended along the top of it. However, this meant that it would take more time (and require more effort) to reach the tipping face with each fresh load of spoil.

- Eventually, it either became too inefficient to extend the tipping line any further, or the spoil reached the boundary of the Midland Railway Company's land[1]. In either case, a new tipping line would be created at an angle to the previous one. As this process was repeated, it created the hub-and-spoke pattern that is typical of many of the spoil tips within the SCRCA., including those shown in the land plan extract below.

Tip: To view a larger version, click / tap the image.

Footnotes

[1] Contract Number 1 (Settle Junction to Dent Head) required the contractor to keep all spoil within the boundaries of the land owned by the Midland Railway Company. The other contracts would almost certainly have included a similar clause.

Acknowledgements

Text by Mark R. Harvey (© Mark R. Harvey, 2017).

Land plan extract uploaded to the SCRCA Project database from the Roy F. Burrows Collection (ref: RFB30031) with acknowledgements to the Midland Railway Study Centre, Jeff Mander, Dave Harris and Mark R. Harvey. Licensed under a Creative Commons 'Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) - see:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/