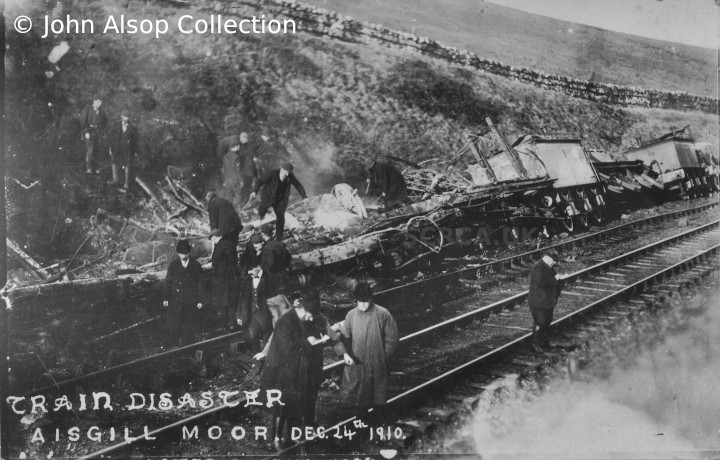

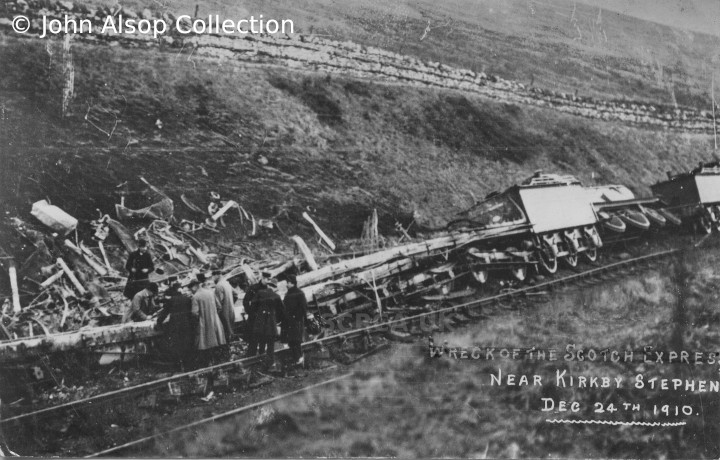

On Saturday, 24th December 1910, Hawes Junction signal box (now Garsdale) featured in one the most deadly accidents to have occurred on the Settle & Carlisle Railway.

During a particularly busy period near the end of his normal 10-hour shift, experienced signalman Alfred Sutton accepted the northbound 'Scotch Express' from Dent and set his signals to allow it to run through the station unhindered. However, he'd 'forgotten' that a pair of coupled light engines were standing on the down main line (near the turntable they'd just used), waiting to head back to Carlisle. When the down 'advanced starter' signal cleared at 5.43 a.m., the drivers of the light engines assumed it was meant for them and they began their journey north. Shortly afterwards, the express ran through the station at about 60 miles per hour.

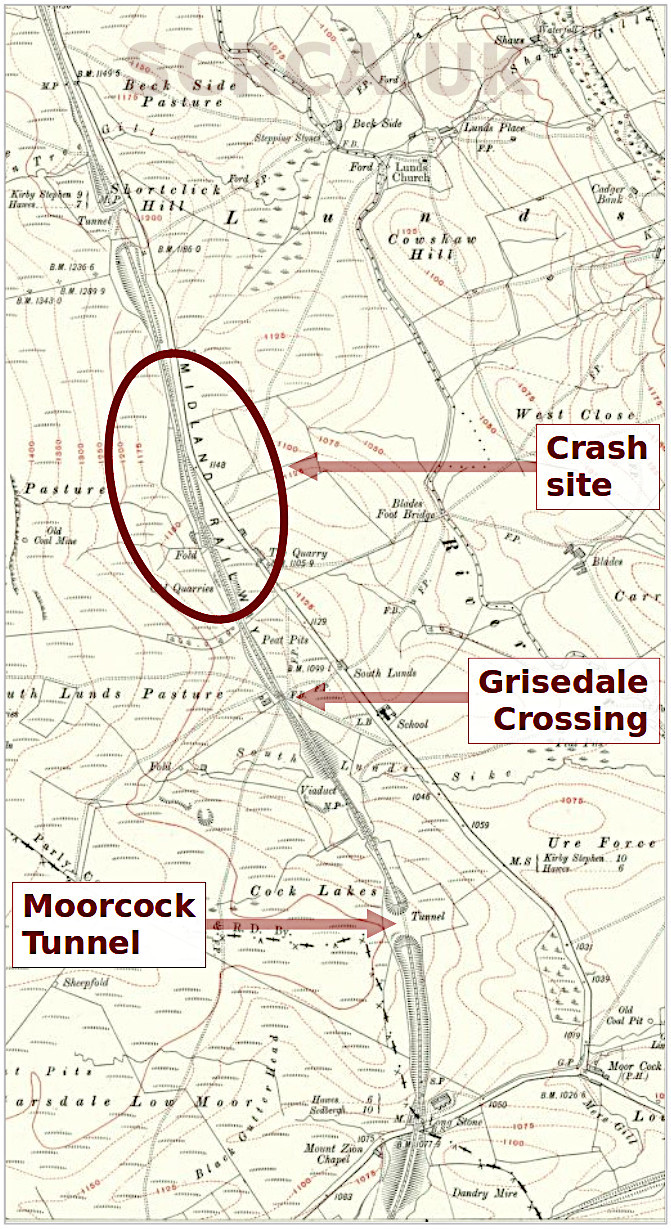

As the express emerged from Moorcock Tunnel and approached Grisedale Crossing at about 5.49 a.m., its driver glimpsed a red light ahead and immediately applied the train's continuous brake. However, the brakes hardly had time to bite before the express ploughed into the back of the light engines.

The official Board of Trade (B.o.T.) accident report paints a vivid picture of the disaster:

"the two front coaches of the express telescoped, and were completely wrecked. Fire broke out, immediately after the collision, in these two vehicles, and eventually all the coaching stock on the train, with the exception of the two rear brake vans, was burnt."

The B.o.T. report estimates that, at the time of the collision, the light engines and express train were travelling at approximately 25 and 65 miles per hour respectively (a closing speed of around 40 mph). As a result of the impact and subsequent fire, twelve people were killed and another thirty were injured.

In the report, Alfred Sutton (the signalman on duty at Hawes Junction) is recorded as saying:

"At six o'clock signalman Simpson (the day signalman) arrived. I went to the north window and noticed a reflection of light in the sky between my box and Ais Gill, and I said to Simpson, 'Will you go to station master Bunce, and say that I am afraid I have wrecked the Scotch Express.'"

The B.o.T. inspector came to a similar conclusion and his report states that:

"responsibility for this accident rests upon signalman Sutton, in that he took no action to remind himself of the position of the Carlisle engines, and did not assure himself by observation that the line was clear before allowing the express to approach."

However, the inspector also assigned blame to the crews of the two light engines because:

"they did not try to attract Sutton's attention by whistling, nor did they in accordance with Rule 55 send back one of their firemen to the signal-box to remind him of their position."

A formal inquest was held at the Moorcock Inn and, during its concluding session on Friday 13th January 1911, the jury returned a verdict of 'accidental death'.

Transcript of news reports from the Leeds Mercury, Monday 26 December 1910

NB: BEFORE reading the transcript below, please note the following:

1) The news reports were written in the 'sensationalist' style that was common in newspapers of the period and some of them contain vivid and POTENTIALLY DISTRESSING descriptions of the scene and related events. Despite this, they have been transcribed in full as they tell some of the human stories in far more detail than the official Board of Transport report.

2) The news reports may contain factual inaccuracies, partly due to the inherent difficulties associated with reporting such events in real-time (and before the full facts are known and / or officially confirmed).

3) The official report specifically addresses some of the inaccuracies and speculations that were circulating in the Press during the period when the official investigation was being carried out.

AWFUL RAILWAY DISASTER IN YORKSHIRE.

MIDLAND EXPRESS WRECKED AND BURNED.

NINE PERSONS KILLED, MANY INJURED.

PASSENGERS ROASTED ALIVE WHILE PINNED DOWN.

LITTLE BABY AMONGST THE FLAMES.

AGONISED PARENTS WITNESS ITS SUFFERINGS.

(By OUR OWN REPORTERS.)

The Midland night express from St. Pancras to Glasgow, which left Leeds at four o'clock on Saturday morning, was wrecked a little to the north of Hawes Junction, with the result that nine persons lost their lives and twenty-five were more or less seriously injured.

After the smash, the wrecked carnages took fire, and several passengers who were pinned down by the debris were roasted to death. The bodies of the victims were so terribly charred that recognition was absolutely impossible, and identification is being sought for in other ways.

Among the passengers were a young couple named Mr. and Mrs. Gray, who were travelling from Hampshire to Glasgow with a baby a few months old. The father and mother escaped with their lives, but the baby was killed, its body being consumed by the flames.

The disaster was caused by the express overtaking and colliding with two light engines which were returning to Carlisle, and the presence of which on the line seems to have been somehow overlooked.

----

Carlisle, Sunday.

Another terrible disaster, awful in the appalling horror of its details, has cast its shadow over the holiday season.

Hardly had the public mind recovered from the shock caused by the terrible colliery disaster in Lancashire, than news of an awful railway collision near Hawes Junction, in the north-west comer of Yorkshire, in the early hours of Saturday morning, deepened the gloom and piled horror upon horror.

There have, alas, been many terrible disasters upon our English railways, and, curiously enough, the worst of these appear to have occurred on the eve of public holidays, but there have been few where all the horror of a devastating fire have added so fearfully to the horrors of a collision as in the disaster which will make Christmas eve, 1910, forever memorable.

The accident happened to the Scottish midnight express from St. Pancras to Glasgow on the Midland line a few minutes before six o'clock on Saturday morning, at a point a mile and a quarter north of Hawes Junction, in the very heart of the mountain waste of the Pennine heights, and a one of the bleakest, loneliest spots to be found upon any railway in England.

The exact spot where the accident happened is about half-way between Hawes Junction and Aisgill, about 65 miles north of Leeds, and 50 south of Carlisle, on the Midland main line.

The railway here is almost the highest in England, being 1,133 feet above sea-level, the highest point on any railway in England being at Aisgill, only a mile and a half away from the scene the disaster, where the elevation is a few feet higher.

The scenery in summer is among the grandest in England, and in winter the wildest and bleakest. A few miles south of where the disaster happened is Ingleborough on the left as one looks north, while on the right stands Pen-y-ghent.

Deep ravines run from mountain range to mountain range, cutting under the railway at right angles, and down these rush mountain torrents, now swollen with the winter rains.

SCENE OF THE DISASTER.

At one moment the train is running over a lofty bridge or some high embankment, as at Went [sic]: at the next it is rushing through some deep cutting that in winter may a source of terrible danger owing to snowdrifts.

It was here that Saturday's awful tragedy was enacted, almost at the very spot, I believe, where some years ago another disaster happened owing to a heavy snow drift in the very cutting where now lies the mass of twisted iron, scarred, distorted by fire - that is, all that remains of the Scottish express.

It is only with difficulty that the exact details of the sad affair have been gleaned, for the railway officials have gone to the extreme, and, I venture to think, unprecedented lengths, in order to prevent representatives of the Press obtaining even the slightest information.

To such an extent has this official hostility to the public been carried that forcible efforts were made to prevent the newspaper representatives even viewing the scene of disaster; and the "Daily Mail" representative, while endeavouring to seek an interview with the general manager of the Midland Company, who was stated to be on the spot at the time, was seized by two railway police, acting under instructions from the police superintendent of the line, and was thrown to the ground and violently removed, while our own photographer, who rested his camera on the boundary wall, was threatened that his camera would smashed if it was not taken down.

A HORRIFYING SPECTACLE.

From various sources, however, the whole sad story has been gleaned, and its details form one of the most terrible tragedies of agonised suffering that has been recorded for many a long year. The spectacle of eight grown human beings and one baby, five months old, imprisoned under the wreckage of a train actually roasting to death, and being charred beyond all possibility of recognition, while their friends and the father and mother of the baby stood helplessly by, hearing their frantic and agonised screams for help, when no human help could possibly be rendered is sad enough make to the stoutest heart ache.

Yet this is absolutely and literally what took place.

EXPRESS FROM LEEDS.

TERRIFIC CRASH IN THE BLINDING STORM.

The train was the usual midnight Scottish express leaving St. Pancras at twelve midnight, stopping only at Leicester, Trent, Leeds, Carlisle, and Glasgow, Bradford and West Yorkshire passengers joining the train at Leeds.

The train left Leeds just after four o'clock with two engines in front, the train from Leeds being in charge of R. J. Oldcorn, of Carlisle, who was driving the pilot engine.

All went well until a second or two before the collision actually occurred, a mile beyond Hawes Junction station.

Here the line makes a slight curve, the north-bound train being the inside of the curve. Passing through brief tunnel it crosses a deep ravine then at once runs into a deep cutting, and on again through another short tunnel.

It was terribly stormy night, with drenching rain pouring down in wind that howled across the moorland, and a thick mountain mist prevailing, but all went well till 5.47 a.m. when suddenly, just after passing the first tunnel, not six yards ahead of him, the driver of the express saw the tail light of engine.

For the fraction of a second his whistle shrieked out, the brakes crashed on, and at the same instant the whistle of the engine in front also gave one shriek, and then the express, travelling at sixty-five miles an hour, hurled itself upon the engines, for there were two front, with terrific impact.

FEARFUL WRECKAGE.

Instantly the whole body of the engine with the tail light, was driven forward with incredible force. It was swept clean off its heavy bogey carriage.

As the engines of the express rushed bodily over the whole of this bogey, the front guard's van, and the two first carriages of the train splintered into matchwood and crumpled like telescopes of paper, while the whole train, which comprised in all nine coaches, kept the rails, rushing and tearing along, ripping up the permanent way, in clouds of steam and smoke, with whistles screaming and passengers shrieking, hurled itself upon the embankment at the side of the cutting, 150 yards from where the first impact took place.

One of the light engines was hurled nearly 400 yards farther ahead before it, too, buried itself shoulder deep in the side of the cutting.

CARRIAGES ON FIRE.

But worse to follow, for in less time than it takes to tell the compressed gas, scaping from the smashed and twisted cylinders, burst into flames, and with horrible rapidity the whole train except the two last coaches were a roaring furance [sic] which no one could approach, and in the midst of which could be seen and heard the injured and imprisoned screaming in their agony, and calling upon Heaven to end their awful sufferings.

The last two coaches, comprising the goods van and sleeping carriage, kept the rails, and were quickly shunted backwards out of the reach of the fire, but the rest of the train was utterly and completely destroyed.

BURNED TO DEATH.

Every scrap of timber, every seat, every piece of clothing, every parcel in the carriages and the front van, and, awful to relate, every person in the whole of the two first coaches was burned to a cinder.

The fire burned till there was nothing left to burn, and only a mass of twisted and distorted wheels and ironwork remained smoking at the side of the cutting.

At the moment of the accident a light engine approached on the up line, and Driver Oldcorn, fearing a further catastrophe, managed to stop the driver.

Such water as this engine carried was used in an endeavour to extinguish the flames, but without the slightest success.

Meanwhile scenes almost too awful to be described were taking place.

There were forty passengers on the train, and some twenty-nine or thirty of these, bruised and cut and shaken, managed to escape.

One man, who was washing in the lavatory, found himself fastened in, but someone burst open the door and released him.

In another case, a man who had been sleeping in a carriage by himself, with his boots off, managed to smash a window and escape from the overturned carriage. He had started from London with six companions, but five of them got out at Leeds.

In still another case, when the floor of a carriage burst open, a sailor fell through and managed to crawl from under the wreckage almost uninjured.

PARENTS AWFUL ORDEAL.

HELPLESS WHILE THEIR BABE WAS BURNING.

But in the first two carriages, terribly different was the fate of the passengers. In one case a man was seen pinioned under one a mass of debris. His screams were awful. The drivers of the engines and others tried to rescue him, but without success. Then some one got an axe and tried furiously to chop away the burning timber, but eventually the heat drove them away.

"God help you! We can do nothing."

"God help me! You've done your best," gasped the man.

But for half hour his groans and cries came from the awful furnace.

In another case a Mr. and Mrs. Gray, Southampton, were travelling with their girl, five and a half months old. and they were compelled to stand helpless while the child was literally roasted alive before their eyes.

The father had literally to be dragged from the burning carriage, where he was trying beat away the fiery timbers, though both he and his wife themselves were injured.

At last, when the fire had burnt out, charred and ghastly remains were picked out of the ruins, laid in little heaps on the embankment, and finally conveyed to the Moorcock Inn, about a mile away.

The injured, who numbered about twenty five, were conveyed to the Cumberland Hospital at Carlisle, or went homewards after being attended by the doctors, who hurried to the spot from Hawes, five miles away, and Kirkby Stephen, eight miles away. The doctors arrived with all possible speed, but it was over hour before they could reach the spot.

THE DEAD.

BODIES TOO CHARRED TO BE IDENTIFIED.

How terrible were the results of the fire may be judged from the following semi-official list of all that remained of the dead passengers.

No. 1. - Adult male. Trousers buttons bore name of an Oxford firm of tailors.

No. 2. - Adult male, probably a young man.

No. 3. - Adult male, evidently of fine physique.

No. 4. - Adult male, wearing a tweed suit of greenish mixture and green and white striped shirt.

No. 5. - Adult male. Belonging's include sovereign purse, containing a seal bearing an inscription showing that it had been presented to Mr. John Highet, junior, by Plantation U.F. Church Sabbath Association, Glasgow, as a mark of esteem.

No. 6. - Adult. Spinal column only. Impossible to state sex.

No. 7. - Adult. Base of skull and right shoulder only. Probably female.

No. 8. - Adult male. Carried silver watch, handkerchief marked "A.R." dark grey suit. Had a week-end ticket from St. Pancras to Old Cumnock, Glasgow. Also possessed an envelope with the name Mackay written across it.

The body the baby seems have disappeared altogether.

On Sunday painful scenes were witnessed

in the chamber death at the little inn. A party of haggard-eyed friends of those who had been on the train and who were missing, went by special train from Carlisle to Hawes Junction.

Among these was Mrs. Mackay, of Old Cumnock, Glasgow, who recognised the watch and handkerchief and a charred envelope as belonging to her husband. She was spared the sight of the charred remains, but broke down utterly as the truth became convincing. She is left with one little girl.

This was the only person identified, though a working man named Stitt told me he was sure his brother, John Stitt, a commercial traveller, working for a London firm, was also among the dead. He was on his way home to spend Christmas with his aged father at Sanquhar, Dumfriesshire.

"I know he's there, but is burnt to a stick. It's an awful sight, said his brother to me, in great distress, after having been to try and recognise the remains.

DRIVER'S VIVID STORY

TRAVELLING TOO FAST TO AVOID CRASH.

A remarkably vivid story of the disaster was told me this afternoon by William Johnson Oldcorn, driver of the pilot engine of the wrecked express. Oldcorn lives with his Wife and family at 50, Melbourne-road, Carlisle.

He was lying in bed with his head bandaged when I called there, and complained of much soreness of body caused by cuts and bruises. He had no bones broken or other serious injury, however, and was deeply conscious of his miraculous escape from death.

I give his story in his own simple and expressive language:

"We had just got round the curve (he said) when I saw a red light directly in front of us. It seemed to be only half a dozen yards in front. I could not see it before as the curve was on the wrong side.

"I knew it was the tail light of an engine, and wondered what it was doing there as we had had all signals off to pass through. The driver of the rear light engine evidently heard us and just gave one touch to the whistle to let his companion know there was something behind. He wanted to get out of the way, but they had not time.

"I did what I could and put brakes on, but we were only half a dozen yards off and were travelling at sixty-five miles an hour. The crash came immediately afterwards.

"I stood on my engine until it came to dead stand. I should think we travelled 15O yards after colliding. We were off the line, and I was all the time expecting should go down the embankment, being in a cutting. Happily we rested the bank.

"Shortly after we stopped Harry Wadeson, driver of the second engine, came round and shouted-

"'Are you alive, Dick'

'I says yes.'

"He says 'Is your mate there.'

"I says 'He went off the engine just before we stopped.'"

ANOTHER ENGINE STOPPED.

After that he said, "There is another engine coming, and I got hold of the whistle and made a loud noise for him to stop. He was on the up-line, but I thought might run into the wreckage.

"It was quite dark, and all lights were out. I was bleeding very badly from a cut on the head. The train was soon on fire, I suppose from gas.

"A good many of the passengers were out. As soon as I got round our tender I saw the coaches were on fire.

"The engine we stopped on the up-line gave us water to try to put the fire out, but it was not sufficient, and the flames gradually got worse. They could not get people out of the carriages. They were fast in.

"It was terrible, altogether, to hear the poor fellows screeching and shouting. The flames were all round the carriages; in fact, after the flames had got hold, you could not stand the bank-side.

"I went back two or three times with our bucket. I had a job to find it. Everything was covered in coal.

DYING MAN'S SCREAMS.

"I struggled and got a few buckets of water, which I threw the flames, but it was hopeless. We noticed particularly one man, who shouted for help, and one of the platelayers shouted to him, ‘We are here. God help you. We can nothing.'

"This man was screaming long after we thought he was dead. He would probably be screaming for half an hour.

"I was principally concerned to try to put out the flames. I knew once the fire got the mastery they were helpless. Trains are all so dry with paint and varnish and gas. They are all inflammable.

"All the coaches were off the road but the last two. If they had remained on the road, we could have dragged them away, as we did the last two.

"The bogie of one the light engines was knocked clean out from under it, and was under one the carriages when we stopped.

"I should think probably that would be what brought the carriages so badly off the road.

"It is wonderful the consequences were not more serious. I don't know how so many us escaped. The carriages were all upright.

"Both engines would have been overturned but for the fact that we were in the cutting. I quite expected when we did come to a complete stop rolling down the embankment."

FIREMAN'S EXPERIENCE.

I also interviewed William McVittie, fireman of the second engine of the express at his home in Carlisle. He estimated the speed the express at sixty miles hour, and said he distinctly saw the signals were clear for them to proceed.

He did not see the light of the light engine, and when the collision occurred he thought it was the first engine that had gone off the line.

"I was crushed up against the fire-box," he proceeded, "and was covered with earth, scraped from the embankment.

"I got hold of something on the embankment and pulled myself up. I scrambled out. All the lights were out, and the carriage next to the engine was ablaze. It was a brake full of parcels. The coach next to that was third class.

"There was so much steam and smoke that I could not see anybody, but I could hear them shouting inside. I heard a voice which sounded to be that of an elderly man, calling out, ‘Oh, dearie me. Get me out of here.'

"Mr. Bunce, station Master at Hawes Junction, then came up, but we could get no water."

ANOTHER FIREMAN'S TALE.

Later in the afternoon I heard the story of Isaac Wannop, fireman on the pilot engine of the express, who, at present, lies in the Cumberland Infirmary here suffering from broken ribs. He is a single man, 33 years of age.

He said "We were going about 65 miles an hour. It was raining cats and dogs, and I noticed nothing wrong until just as we emerged from the tunnel.

"Then I saw a red light along the line in front of us, and said, 'We are into something.' My mate slammed on the brakes, and almost immediately there was a most terrific crash. I have never heard anything like it in my life before. "Then I found myself lying down the bank. When I picked myself up there was a tremendous flare from the carriages. I could see there were some people under.

"I thought I would go to the signal-box Aisgill, and staggered along towards it. I must have fallen unconscious, for I awoke later in a platelayers' hut and saw the train burning like mill."

Wannop's condition is not regarded as dangerous.

ACTOR GRAPHIC NARRATIVE.

Mr. Edmund Salley, member of the "Big Bird" company, performing at the Haymarket Theatre, London, who was travelling by the ill-fated train to his home in Galashi8els, gave a graphic story of the calamity on reaching here.

He was in the rear compartment and had gone into the lavatory to wash, preparatory to arriving at Carlisle. Suddenly he was thrown forward violently against the mirror, smashing the glass and cutting his nose and chin.

On getting outside he found one was injured in his compartment.

He said: "Our attention was immediately directed by the piteous screaming of a young married woman, who was shouting for her child, which had been pinned underneath the partition. "Her husband was making frantic efforts to extricate the child from its perilous position, but the fire spread with such remarkable rapidity that we had absolutely to drag him away in order save his own life.

"The father of the child had himself a marvellous escape. When the collision occurred he fell clean through the flooring of the carriage. I went into the carriage and saw two men pinned down, moaning with pain, but could not get them out."

The first light engine was driven by a man named Scott, who, in an interview, said they waited an hour at Hawes junction, as he thought for the express. An excursion passed, and then the signal dropped to allow them to proceed.

"TOO LATE."

DRIVER PILOT ENGINE'S STORY.

"I whistled an acknowledgment," he proceeded, "and we entered the main line for the return journey to Carlisle. We were about a mile the way, travelling about thirty miles an hour, when I heard the whistle of an engine behind.

"I looked round and saw the lights of an oncoming express. I immediately put on full steam in order increase our speed and thus lessen the impact, but it was too late. The express was upon us.

"The collision lifted me off my feet and landed me on my back on the coal. The buffers of the rear engine penetrated our tender."

FIRST THE SPOT.

The first to get the scene of the disaster was railway man named Robert Field, who lives in one of a row of cottages near the spot. He related to me yesterday that he was just coming downstairs when heard two loud whistles. He said to himself, "Here's wrong."

Then he heard a great crash. He proceeded to the spot in all haste, and saw what had happened. He at once went for an axe and a crowbar for the purpose of liberating the people in the wreckage, but when he returned there was so much smoke and fire that he could not get near to them.

PAINFUL INTERVIEWS.

RELATIVES AND FRIENDS VISIT THE DEAD.

On Saturday evening the remains of the nine victims of the catastrophe were removed on stretchers to Moorcock Inn, close to Hawes Junction, there to await identification and the inquest. In the meantime relatives and friends of the missing ones in Scotland had been anxiously inquiring for news of their visitors, and early yesterday morning a special train arrived at Aisgill from Carlisle conveying to the scene of the tragedy a number of sorrowing, despairing men and women, whose errand was to ascertain beyond all doubt the fate of their unfortunate kinsfolk.

Accompanied by two officials of the Midland Railway Company, they looked for a few brief seconds upon the fateful spot, where now huge cranes and a hive of busy workers were slowly, but surely, removing all traces of the fearful smash, and then proceeded on foot to Moorcock Inn, about a mile and a half ahead, where their respective statements were taken down in writing by the company representatives. It is feared that Mr. Maxwell, aged 22 years. the only son of Colonel Maxwell, of New Galloway, Kirkendbrightshire, lost his life in the train wreck and fire.

Colonel Maxwell was among the band of inquirers. The visitors also included the two brothers of John Stilt, aged 44 years, commercial traveller, London, who journeyed by the ill-fated train, but never reached his destination.

A Mr. Mackie, of Old Cumnock, is believed to amongst the killed, and his young wife and her brother were included in yesterday's mournful party. It was understood that another young lady, whose name was withheld, had lost her sweetheart in the collision.

At the conclusion of their interviews with the railway company's representatives, the visitors were conducted to the room where the remains had lain since the previous evening, and some heartrending scenes were witnessed.

One young lady was led the doorway in a faint, but recovered on gaining the fresh air. Some of the men, too, were visibly affected.

INQUEST OPENS TO-DAY.

The inquest will be opened before the North Riding Coroner at one o'clock to-day, at the Moorcock Inn, Hawes Junction.

Police-Inspector Rutter, of Hawes, was engaged yesterday in summoning a jury, and in view of the scattered and isolated nature of the district, his task was not an easy one.

SHEPHERD'S VIVID STORY.

IMPRISONED PASSENGERS' APPEAL FOR HELP.

One of the first to reach the scene of the disaster was a shepherd, Arthur Ashton, who gave the following account of his experience:

"My house is only a short distance away, and I can hear all the trains that pass quite distinctly. Shortly before six o'clock this morning I heard an express rattling by, and then the noise of a great shock. At the same time I saw from my bedroom window a flash of fire.

"I hurried downstairs and made for the railway. A neighbour went along the same time. It was just six o'clock as I turned out. Darkness still enveloped the countryside, and rain was falling smartly. On reaching a point just south of the tunnel to which I was directed by the flames and noise of the engines, I first spoke to a man standing in the cutting, who proved to be one of the express train drivers. I asked him what had happened, and he replied that they had run into a light engine. His head was bleeding.

"I then turned my attention to the wrecked train. The second engine was on fire, and the first two coaches seemed to have run into each other and had fallen on their sides. The others maintained their upright position on the metals.

"A few passengers had got out of the train and climbed the bank side, while others had kept to their seats. Several of them had sustained injuries in the collision but so far as I could learn they were not seriously hurt, and practically all were able to leave the train unassisted. There were very few ladies among the travellers.

"Three persons - a gentleman, his wife, and another gentleman - went to my house for shelter, all three being very much upset. The two former made their escape with some difficulty, and were broken-hearted at having lost their little child in the smash. The poor man collapsed immediately on entering the house.

"It soon became evident that our services were most needed on behalf of those imprisoned the foremost carriages, to which our attention was directed by moans from those imprisoned in the wreckage. In another part a man was calling out for help, saying that could make his way out if only a road could be made for him.

"One of the passengers who had escaped injury asked for an axe to brought to clear the way to the sufferers. A number were conveyed to the spot, and then we set to work, forcing a passage through the doorway.

"We hammered and pulled away to try and get the poor people out, but the fire prevented us, and were obliged give up. Another heartrending case was that of a sailor and a medical student, who were both fast asleep when the accident occurred. The sailor managed to get out, but the student was jammed between two partitions. They tried every means to get him out, but the fire swept up and drove them away. The student thanked them for what they had done for him, and asked them if they would send word to his mother. The fire soon silenced his voice for ever.

"During the search among the debris of the front carriages, where the human remains were found, various articles of jewellery and other personal belongings were collected, including some children's toys, which, doubtless, belonged to the little one who was said to have perished.

"So soon as it became evident that the last remains had been got out the railway staff set to work clearing away the wreckage and repairing the permanent way. The down line had been much damaged for a considerable distance, especially from the point where the collision occurred to where the two light engines had been dashed forwards - a distance of from 150 to 200 yards.

PASSENGER'S ESCAPE.

SKIPTON TRADER'S STORY.

Mr. William Wrathall, eldest son of Mr. Robert Wrathall, the well-known cattle dealer, of Farnhill Hall, near Kildwick, who joined the train at Skipton, had a miraculous escape.

Breaking a window, said he, I was soon free, escaping with nothing more serious than a few small cuts on my hands. I left two overcoats in the compartment, besides losing my hat. I also lost all my money in some mysterious manner, probably in scrambling through the window.

It was raining heavily, besides being pitch dark, and I managed to improvise a cap from one of the green lamp covers used for shading the lights in the carriages.

A man crept from underneath the carriage near me. He had apparently dropped through the bottom of the compartment next to the one I occupied. He was travelling with his wife and child. The woman was got out with all speed, but she had evidently been badly cut by broken glass, and I found a quantity of the blood on my coat sleeve. I then heard the unfortunate couple had left their child in the compartment. Their distress was pitiful, the father making frantic efforts to extricate the child, but it was pinned down by the partition of the compartment. I could hear it screaming, and once caught a glimpse of the little one, but nothing could done to release it.

The fire, which had now broken out, spread very rapidly, fanned by the strong wind, and the terrible plight of a man whom I saw pinned the woodwork was rendered more acute by our inability to get him out before the oncoming flames ended his sufferings. He would be fully an hour in this awful position, and was fully conscious to the last.

The last words we heard him utter were, "Good-bye and God bless you. You've done your best for me."

I remained on the scene helping remove mail bags and parcels from the van in the last coach (the only one which had kept to the metals and which was from the remainder of the train) until about 8.45 a.m., when I was conveyed to Hawes Junction on a light engine, and reaching there telegraphed home that I was safe, a fellow-passenger lending me the sixpence to pay for the wire. With other passengers I then went the house of the signalman, whose wife made breakfast for us, although her distress was touching to all.

"NUMBER FIVE."

IDENTIFIED BY AN INSCRIBED SEAL.

A Glasgow telegram says the identity of one victim was established at Glasgow last night. Relatives intimated that the remains, labelled number five, were those of John Highet, jun., 40 years of age, who held an important position at the head-quarters of the London Assurance Company. He had been resident in the Metropolis for several years, having been promoted from the Dublin office, to which originally went from Glasgow.

Several brothers reside in Glasgow, and they and other relatives had proceeded to Stewarton, Ayrshire, where, with their aged father, they were to hold a family gathering for the homecoming of the son John, who was unmarried.

CONDITION OF THE INJURED.

All the injured passengers passengers who were able to travel to Glasgow by the relief train were reported last night to be improving.

Mr. and Mrs. Gray, who lost their baby, have recovered somewhat from the terrible shock, but they are almost inconsolable over their tragic bereavement. Both sustained personal injuries, and they are confined to a relative's house.

OFFICIAL STATEMENT.

GENERAL MANAGER'S REGRET.

The General Manager of the Midland Railway, Mr. Guy Granet, has issued the following statement:-

"I regret to have to state that the 12 midnight train from St. Pancras to Scotland, when proceeding north of Hawes Junction, came into collision about six o'clock this morning with two light engines which were coupled together and running in the same direction.

"As a the result of the collision, the first two carriages of the Scottish train telescoped and nine passengers were killed. Several others were injured, but, as far as is known, not seriously, and these proceeded to Carlisle by special train.

"Unfortunately, after the collision the carriages took fire. The passengers who met with their death have not yet been identified."

BOARD OF TRADE INQUIRY.

It is officially stated that the Board of Trade have appointed Major Pringle, R.E., to hold an inquiry into the cause of the collision.

No official statement bearing on the cause of the disaster, telegraphs the Central News Derby correspondent, will be issued until the Board of Trade inquiry, which opens to-day, is held.

Partial transcript of a news report from the Leeds Mercury, 28th December 1910

RESTORING THE LINE.

Steadily, patiently, and methodically, the officials and employees of the Midland Railway have been labouring for three full days and nights at the tremendous task of removing the long line of wreckage which the dire disaster of Christmas Eve had left in its trail on Aisgill Moor.

It has entailed an enormous amount of strenuous toil. rendered all the more trying and arduous by a sudden visitation of Arctic weather, which laid a thick pall of white upon all the neighbouring heights, including Wild Boar Fell, Swarth Fell, Baugh Fell, and High Seat, all of which attain an altitude of over 2,000 feet. At the comparatively low level of 1,100 feet, which about represents the elevation above sea level of Aisgill Moor and its lonely railway track, the ground was held in the firm grip of a bitter frost, which drove the hardy mountain sheep from their craggy peaks in search of sheltered pasturage among the home enclosures.

It was with hearts and bodies steeled against cold and hardship that the brave engineers and their associates of the pick, shovel, and crowbar, plodded hour after hour, and relay by relay, at the grim task of clearing and repairing a line section three-hundred yards long, containing by way of wreckage, four broken and overturned engines and the remains of an express load of coaches, and necessitating after the obstruction had been cleared away the reconstruction of the entire length of one track.

A visit paid to the fatal spot yesterday, showed that the more forbidding stages of the giant struggle had been successfully passed and the end of the task was in sight. The disabled locomotives had not only been pulled into an upright position upon the metals by the aid of powerful cranes, but removed to a siding north of Shotlock Tunnel, where they stood like grim sentinels keeping guard over the tragic spot which had shorn them of their power.

Partial transcript of a news report from the Leeds Mercury, 30th December 1910

FUNERAL OF THREE VICTIMS

The inquest proceedings were adjourned for half an hour in the afternoon, when the interment of the remains of three of the victims took place in the parish church graveyard.

The scene was full of sad pathos. The three coffins were carried through the village to the church, which stands on high ground, villagers and railway employés, and behind walked the relatives of some of the missing men, many inhabitants of the village, and the officials concerned the in Coroner's inquiry.

A tragic figure in the procession was Signalman Sutton, who walked with bowed head in company with some of his friends. A short service in the church preceded the final rites at the graveside.

In the course of brief and appropriate address, the Vicar (the Rev. T. E. Ellwood) referred to the shadow of a great sorrow that had fallen upon them in consequence of the appalling catastrophe at Aisgill. The most respectful sympathy and regrets of all were offered to the bereaved and saddened hearts. The sorrow of the sufferers and bereaved had made the hearts of our common life beat the more audibly. He wished to offer, in the name of all present, as well as in his own, deep sympathy with him whose very human mistake was the cause of the sad occurrence. He spoke quite advisedly when he said that those who knew the man the best would be the most ready to forgive the inadvertence, and hold out to him the right hand of sympathy.

The church choir took part in the service and the hymns sung were "Sleep thy last sleep" (the hymn sung on the occasion of King Edward's funeral) and "Jesu Lover of my Soul.'"

Though the evidence of identification was of the slenderest, it is believed that the remains interred to-day were those of John Stitt, of Ilford (in regard to whom evidence was given at the inquest); Daniel James Lamont (16), the son of a Scottish minister and Wm. Bell Ridell (30), of 27, Larkhallrise, Clapham. London.

FUNERAL OF SCOTTISH VICTIMS.

Three of the victims of the disaster are to buried in Scotland to-morrow - the remains of Mr. Maxwell in Kells Churchyard, New Galloway, and those of Hugh Mackay and Donald Mackay in adjoining graves in Old Cumnock Churchyard.

The shells containing the remains have been brought to Leeds to be placed in oak coffins by the Undertakers, acting for the Midland Railway Company, and they will be sent forward to-morrow morning by the four o'clock express, the corresponding train to that which met with disaster last Saturday morning.

Transcript of a news report from the Leeds Mercury, 11th January 1911

SIFTING WRECKAGE AT HAWES.

VALUABLES DUG OUT OF DEBRIS.

CLUES TO IDENTIFICATION.

From our Own Correspondent.

Kirkby Stephen, Tuesday.

I paid a visit to the scene of the disaster to-day, when comparatively mild weather prevailed, despite the fact that snow lay thick on all the adjacent mountain peaks.

I found that the four engines damaged in the collision, which on the occasion of my last visit were standing in a siding near Aisgill signal cabin, had been temporarily repaired and removed to Leeds. One or two of the locomotives would not travel until new wheels had been fitted, while two of the three tenders had to be taken away upon wagons.

I ascertained that the train wreckage deposited on the embankment side in the fatal cutting had been scrapped and conveyed to the railway company's headquarters at Derby, the final consignment having left by special train last Sunday.

Since that time a small body of workmen from Settle has been searching among the ashes and ballast lying outside the down line for traces of personal belongings that may yet remain likely to assist in elucidating some of the mystery connected with the tragedy.

The method employed was to pass the ballast through a large riddle with a mesh sufficiently fine to retain all but the smallest substances. The operations were being conducted under the supervision of a railway police-officer, who kept a sharp look-out for relics.

Some very important evidence has been unearthed as a result of a two days' search, and as a considerable portion of the affected area still remains to be examined, further discoveries may be expected.

Chief among the articles recovered was a revolver, upon the barrel of which were stamped the words, "Colt's Patent, Hartford City, U.S.A." The weapon has evidently been where the fire was hottest, judging from its appearance when brought out from among the debris.

Not far from the same place a gentleman's silver watch was picked up, bearing evidence of having passed through a raging furnace. It would be a difficult matter for any one to identify the watch in its present state unless by the number on the inside of the case, which, so far as I could ascertain, was 82574.

Part of the outer case of a gentleman's gold watch, chastely engraved, was found near by, together with a bunch of keys, to which was attached a Universal Key Registry tab, offering the usual reward on the keys being returned to a police officer.

Two complete steel watch chains were turned-up at different points, also part of what appeared to be a silver chain.

Presumably none of the articles recovered had belonged to a female, and the search up to now has produced nothing to throw light on the identity of the lady supposed to have perished.

Board of Transport report, published on 31st January 1911

A digitised copy of the official report by Major Pringle, R.E. can be downloaded in PDF format from:

https://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/eventsummary.php?eventID=78

This document sets-out the findings of the official investigation into the accident (including the statements obtained from key witnesses) and sets-out some suggestions for consideration by the relevant parties. In addition to providing the key 'facts', it also provides a fascinating insight into both social history and local railway operations.

Acknowledgements

The news report has been transcribed by Mark R. Harvey from a digital image of the original (downloaded from the British Newspaper Archive - https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/) and a microfilm version of the original (accessed at Leeds Central Library).