The production of Gypsum and its associated minerals has taken place in the Eden Valley between Carlisle and Appleby for more than 350 years.

What is Gypsum?

Gypsum and its associated minerals are forms of Calcium Sulfate. The main minerals are:

- Gypsum (CaSO4.2H2O), the hydrated form and

- Anhydrite (CaSO4), the anhydrous form.

Other forms of Gypsum are:

- Alabaster, a very fine-grained material and

- Selenite, a crystalline form.

Where does Gypsum come from?

In the Eden Valley these minerals occur in beds in a series of rocks known as the Eden Shales which were deposited during the latter part of the Permian era, approximately 250 to 270 million years ago.

The deposits were formed by the evaporation of mineral rich sea water and together with other minerals such as rock salt are referred to as Evaporites. Quarrying and mining of these deposits has taken place at several locations in the Eden Valley.

In more recent times a synthetic form of Gypsum known as Desulfogypsum has become available. It is derived as a by-product of some industrial processes, notably the desulfurisation of flue gases at coal fired power stations. The availability of this source is now declining as power generation moves away from coal fired plants.

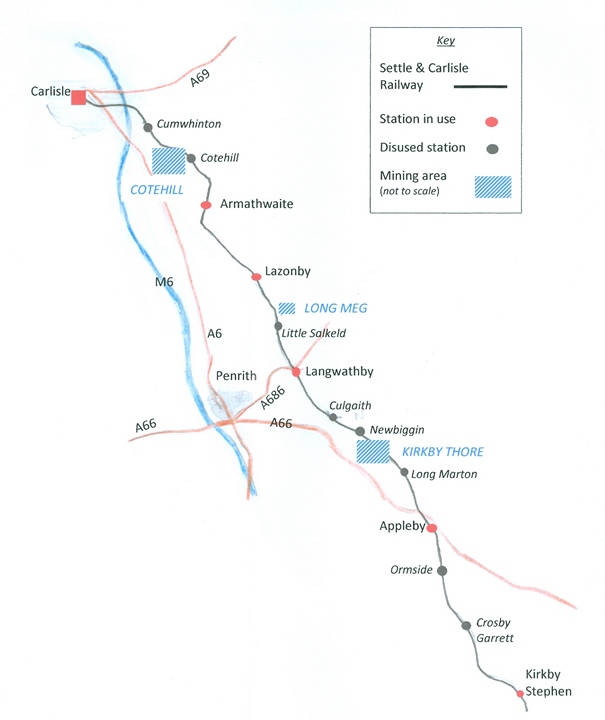

There are three areas in Cumbria, close to the Settle-Carlisle Railway, where production of Gypsum has taken place namely Kirkby Thore, Little Salkeld (Long Meg) and Cotehill. Figure 1 shows the locations of these areas.

Each of these areas has been described in more detail in a set of accompanying articles (see 'Further Reading' section for links).

What is Gypsum used for?

Gypsum is used mainly in the construction industry as the main constituent of plaster and plasterboard. It is also used in the manufacture of cement. Lesser uses include the manufacture of Plaster of Paris and fillers in paper and paint.

Anhydrite is used in the production of chemicals, particularly sulfuric acid and fertilisers. When mixed with Gypsum it is also used as a retarder in cement.

Alabaster has been used for carving architectural features and statues. It was also used in the manufacture of ornate lamp shades.

How was it extracted?

Initially in the Eden Valley, Gypsum was extracted from small quarries at a number of locations. The earliest records of extraction date from around 1685. As demand increased, the limitations of quarrying became apparent. The Gypsum beds are not always horizontal and at several places dip away from the initial quarry face. This means that more material must be excavated and disposed of before the Gypsum itself can be exposed and extracted. This material is known as overburden. The extraction becomes uneconomic when there is too much overburden and a change in extraction technique to mining is required. At some sites the change to mining was also driven by a lack of working space or land ownership issues.

The majority of the mining for extraction was carried out by driving tunnels (known as drifts or adits) through the deposits. These were often inclined (up to 1 in 6) to follow the Gypsum deposit. Although some shafts were sunk for exploration purposes or ventilation, they were not used for large scale extraction because the deposits were at a relatively shallow depth when compared for example with coal workings.

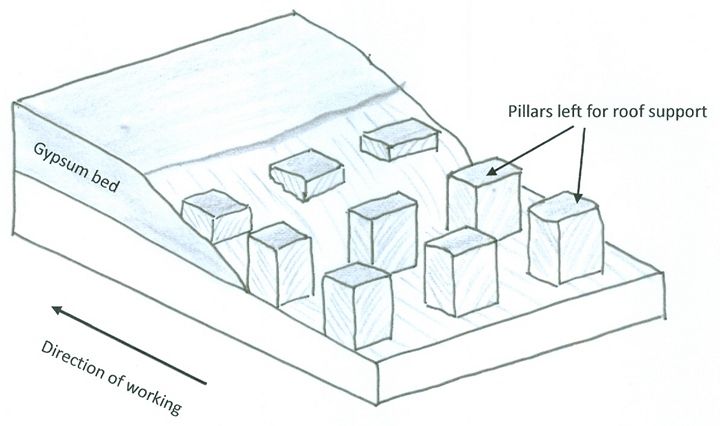

Further tunnels (roadways) perpendicular to the main drift are then driven to extract the mineral. These secondary tunnels, usually around 6.5m wide are driven on a grid pattern and are separated by pillars of mineral left in-situ (usually about 6.5 to 7 metres square) which support the roof. This is known as pillar and stall working and an example is shown in the diagram in figure 2.

Great care has to be taken with this type of mining to ensure that sufficient material is left in place as pillars to adequately support the roof. A balance between extracting the maximum amount for financial gain and leaving material to provide safe support needs to be struck otherwise a collapse will occur. This happened once in the Kirkby Thore area, resulting in the pillar size being doubled.

Most of the mine workings had a tramway system, usually 24” gauge. The extracted material was loaded into tubs and removed from the mine. Initially tubs were pushed by hand but small locomotives soon came into use in the twentieth century.

Once outside the mine the extracted material was crushed and sent for further processing.

Who extracted Gypsum?

In the early stages of the industry, Gypsum was found in exposures on the ground surface which were then developed into small surface pits and quarries of which there were many. Each of these was usually worked by a few local men, some of whom were builders or plasterers. As demand increased, larger scale operations were needed and by the mid 1800’s a number of companies had been established which were locally based. Despite the demand for Gypsum there was some financial uncertainty and in 1911 the three largest companies, Howe & Co., Robinson & Co. and the Long Meg Plaster Co. amalgamated to form the Carlisle Plaster and Cement Company. Due to under-capitalisation, this company went into receivership and in 1918 was taken over by the Gotham Company who produced Gypsum in the Nottingham area. It operated independently of Gotham until 1939 when Gotham itself was taken over by British Plaster Board (BPB). BPB had been established in 1917 by McGhies of Kirkby Thore to manufacture and distribute plasterboard. Through a series of mergers by the 1960’s BPB became the sole producer of Gypsum and manufacturer of plasterboard in the UK. It had also acquired other manufacturing interests and in 1964 amalgamated all its Gypsum interests into British Gypsum, a subsidiary company. In 2008 BPB Industries was taken over by the multi-national Saint Gobain Group and today British Gypsum retains its identity as a subsidiary company within the Group.

The relationship with the Settle-Carlisle Railway

From the early years of its operation, the railway provided a convenient and essential means of transporting raw materials and products from the mines and quarries in areas which were remote and relied principally on horse drawn transport. It enabled large increases in output to be achieved. In later years, the railway also provided the means to transfer materials between the mining sites and to import Desulfogypsum for processing at Kirkby Thore. The three production areas in the Eden Valley each had standard gauge internal railway systems with locomotives and their own sidings connected to the Settle-Carlisle Railway. The workings at Kirkby Thore and to a lesser extent Cotehill, extended beneath the railway causing some ground movement which at various times gave rise to speed limits being imposed until tracks could be realigned. In these areas ground movement affecting roads, property and agricultural land was not uncommon even after mining ceased.

Further Reading

The following articles expand on the theme of the Gypsum industry in the Eden Valley by focussing on three specific areas between Appleby and Carlisle that currently have, or or that once had, a direct connection with the Settle-Carlisle Railway:

- Gypsum production in the Kirkby Thore area

- Long Meg Mine, Little Salkeld

- Gypsum production in the Cotehill area

A comprehensive account of Gypsum production in Cumbria can be found in the book “Gypsum in Cumbria” by Ian Tyler (Blue Rock Publications 2000, ISBN 0 9523028 4 5).

Some details and photographs of the internal railway systems can be found in the book “Industrial Locomotives & Railways of Cumbria” by Gordon Edgar (Amberley Publishing 2016, ISBN 978 1 4456 4833 0).

Further details and photographs of the internal railway systems at Cocklakes and Long Meg can be found in the book “Industrial Railways and Locomotives of Cumberland” by Peter Holmes (Industrial Railway Society 2017, ISBN 978 1 901556 95-7).

Details of sidings and connections to the S&C railway can be found in “Stations & Structures of the Settle & Carlisle Railway” by V R Anderson & G K Fox (Oxford Publishing Company, 2nd edition 2014 ISBN 978 0 86093 662 6).

Background information on the formation of the Gypsum companies can be found in “BPB, The History of BPB Industries” by David Jenkins and published by the company in 1973 (ISBN 0 9502572 0 6).

Acknowledgements

This article was researched and written by David O'Farrell specifically for the SCRCA web-portal. The illustrations were drawn by the author.