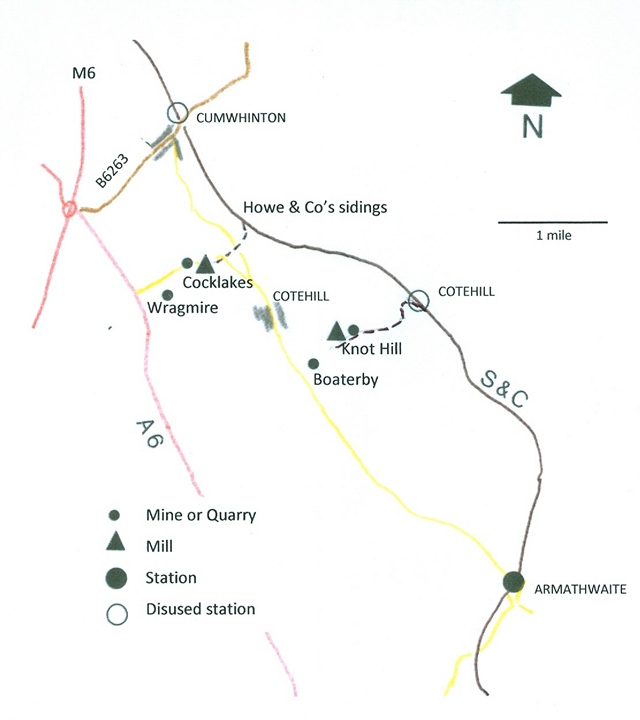

Quarrying and mining has been taking place around the village of Cotehill for some 400 years, the earliest date recorded for the extraction of Gypsum being 1685.

Initially Gypsum was found in exposures on the ground surface which were then developed into small surface pits and quarries of which there were many. Each of these was usually worked by a few men, some of whom were builders or plasterers. Some of the workings produced Alabaster and there is evidence of a local builder using Alabaster for a floor in 1731.

Operations became more commercial around 1830 with leases being granted to several partnerships.

In 1838 a Carlisle solicitor, John Howe, established John Howe and Company, Alabaster Dealers and makers of plaster of paris, at premises in the city centre. He went into partnership with John Pigg a landowner of Cotehill, to extract and refine Gypsum. Together they opened a quarry near Cotehill and due to increasing demand, expanded their operations. Pigg left the partnership around 1850 but further quarries were opened as the earlier ones became worked out. In the early 1860’s a quarry was opened at Cocklakes.

During this time, the excavated material was hauled by cart into the premises in Carlisle for processing. In 1862 the factory was expanded but the need to transport the raw material meant that processing was time consuming and it became apparent that a processing mill at the quarries would be more cost effective. Thus around 1864 a mill was constructed at Cocklakes which also had the capacity for processing material excavated from other local quarries and for projected expansion.

By 1873 production had increased to the extent that the mill needed to be upgraded to cope with the volume of material. This expansion coincided with the construction of the Settle-Carlisle Railway and shortly after the railway’s opening in May 1876, Howe and Company began negotiations for the construction of a siding to serve the mill and quarries. Agreement was reached on 29th December 1876 for a siding at milepost 302 + 75ch controlled by a signal box which had 12 levers with 2 spares.

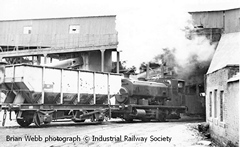

Initially material was brought by horse and cart to the loading dock from the mill which was approximately half a mile away. However, this was soon superseded by the laying of a branch line from the siding to the mill by 1880 and the company purchased its first locomotive. This locomotive was a standard gauge 0-4-0 saddle tank and was given the name John Howe.

The name was transferred to a new standard gauge 0-4-0 saddle tank locomotive in 1908 when the original was taken in part exchange. The second John Howe lasted until 1970.

Other steam locomotives at Cocklakes were Harold (bought second-hand in 1924 and scrapped c1943),J.N. Derbyshire (new in 1929), WTT (1942) and WST (1954). In the latter years of operations these locomotives were moved between other gypsum mines as required.

In 1968, the first of three new diesel hydraulic locomotives arrived followed in 1970 by two more. Again these locomotives were moved between Cocklakes, Long Meg and Kirkby Thore as required.

Another large operator in the area was Joseph Robinson & Co. who had been quarrying at Wragmire and Knot Hill since 1837. At that time Robinson had also taken a lease on a corn mill at Denton Holme in the city centre which was used to crush and process the output from the quarries. In addition, the mill made biscuits and bread, in competition with Carrs (who still produce biscuits in Carlisle today).

Whilst it may seem strange that mineral processing and food production were taking place simultaneously in the premises, it was not unusual at that time. Substances, including fine white powders (such as salt, alum, ground chalk, inferior quality flour and possibly Gypsum), were known to be added to flour sometimes to reduce production costs and make bread cheaper to buy. This practice of adulterating food occurred until the introduction of food regulation in the 1880’s and it’s possible that could have been happening here.

By 1858 the demand for Gypsum was such that a custom-built mill was erected at Upperby, on the outskirts of the city and closer to the quarries. Joseph Robinson had been killed in an accident about this time and the business was passed to his nephew John Thomlinson. A further quarry known as the Thomlinson Quarry was opened at Knot Hill around 1865 as some of the earlier quarries were by now exhausted.

In 1877 the company decided on further expansion and constructed a new mill for crushing and calcining the Gypsum at Knot Hill, adjacent to the quarries. This removed the need to transport materials to Upperby which had been costly and time consuming.

The expansion also included constructing a link to the S&C from the new Knot Hill mill. Agreement with the Midland Railway was reached in 1877 and a connection was made immediately to the south of Cotehill Station (milepost 301+11ch). An 0-6-0 saddle tank locomotive named Inglewood was acquired to transport materials from the mill. This connection to the railway, referred to as Robinsons’ siding, was removed in 1940 and the only visible remains of it today are the parapets of the bridge shown below.

By 1881 Robinson & Co’s original quarries were worked out and the Thomlinson Quarry was becoming more difficult to work so the development of a new quarry nearby at Boaterby was begun. This went into production in 1885 and produced 10,000 tons of Gypsum in its first year. To ensure future expansion a new lease was ratified with the Duke of Devonshire for the Cotehill land and 33 acres of new land acquired from the Earl of Lonsdale near Kirkby Thore.

Demand for Gypsum was increasing and by 1898 Boaterby had reached its limit as a quarry. Consequently, a drift (adit) was driven into the quarry face to follow the Gypsum deposit and the extraction method switched to mining using pillar and stall methods.

Meanwhile since 1879 Howe & Co. had sunk several exploratory shafts to confirm the presence of Gypsum in the locality of Cocklakes Quarry and by 1890 a large adit was driven into the north face of the quarry and pillar and stall extraction began. Also, around this time the Cocklakes works was enlarged to about twice its original 1870’s size.

Despite the demand for Gypsum there was some financial uncertainty and in 1911 Howe & Co amalgamated with Robinson & Co and the Long Meg Plaster Co. to form the Carlisle Plaster and Cement Company. Development continued under the new company and a replacement signal box with a 20 lever frame was installed at the Howe & Co’s sidings in 1916.

Due to under-capitalisation, the company went into receivership and in 1918 was taken over by the Gotham Company of Nottingham who established a separate company to operate the mines. Around this time, rock from Kirkby Thore was being transported by rail for processing at Cocklakes Mill.

Resources at Boaterby were almost exhausted by 1920 and mining operations ceased leading to the closure of the Knot Hill processing mill with the employees moving to Cocklakes. By 1922 all quarrying had ceased and production came from the Cocklakes mine.

In 1923 a contract was won to supply 2,000 tons per month of Anhydrite to ICI at Billingham to produce ammonium sulfate. This enabled the company to invest in new mining equipment to increase productivity. However, this only lasted until 1925 after 40,000 tons had been provided when ICI found alternative sources. At this time there were also developments in the range of types of plaster being produced which also increased the output of the mill.

In 1935 the Gotham Company was taken over by British Plasterboard who were keen to expand operations. The underground workings were expanded by the driving of a new adit and in 1937 construction of a new plaster board plant was underway.

At the start of the war the plaster board plant was closed but during 1940 there were serious shortages of Anhydrite to manufacture sulfuric acid so Cocklakes was brought back into production to supply a new sulfuric acid plant at Prudhoe near Newcastle which was adjacent to both the River Tyne (for water supply) and the Carlisle to Newcastle railway which enabled direct rail deliveries from Cocklakes.

Labour was in short supply as Gypsum mining was not a reserved occupation during the war. There were a number of prisoner of war camps in the area and Italian PoWs were used to supplement other sources of labour. By 1943 the mine was working 24 hours per day. Additional locomotives were acquired for the internal rail system and the size of the company sidings was increased necessitating the widening of Bridge 342 and the fitting of a 30 lever frame in the signal box.

After the war, the supply of Anhydrite to Prudhoe continued for a few years and a further contract to supply 4,000 tons per week to the United Sulfuric Acid Corporation Ltd at Widnes was begun. The demand for Gypsum had increased considerably with the boom in new housing which supported further developments in production and extensions to the mining areas. Underground locomotives were also introduced around this time.

By the late 1950’s production was still increasing and two loaded trains per day were leaving the Howe & Co’s siding. Raw materials from Long Meg or Kirkby Thore were also brought in by rail for processing in the mill.

By 1966, the mine had been extended to its limit reaching faulted ground and the reserves had effectively been worked out. The mine closed on 20th July 1966. Production continued at the mill using imported material and this continued until the early 1980’s when the cost of importing material became uneconomic so the plant was removed and the buildings demolished.

Since the time of the closure there has been ground settlement around the old quarry and works which has necessitated the closure of some minor roads and the realignment or truncation of others. There are few remains visible from publicly accessible areas.

Two of the Andrew Barclay 0-4-0 ST locos which operated on the standard gauge internal rail system are preserved at the Ribble Steam Railway (https://ribblesteam.org.uk/). These are John Howe dating from 1908 and J N Derbyshire from 1929.

The rail connection to Howe & Co’s sidings was lifted when the works closed but most of the track bed is now a public footpath and the low embankment is still visible where the track climbed away from the railway sidings. An ungated road crossing is also visible on one of the now closed minor roads near the site of the works.

Image Gallery

Image 1

Brian Webb photograph © Industrial Railway Society.

Image 2

Image 3

Photo © Cumbrian Railways Association.

Image 4

Brian Webb photograph © Industrial Railway Society.

Image 5

Image 6

Further Reading

For a general introduction to the gypsum industry in the Eden Valley and its relationship with the S&C, see The Gypsum Industry and the Settle-Carlisle Railway. You may also find the following of interest: Gypsum Production in the Kirkby Thore Area and Long Meg Mine, Little Salkeld.

Acknowledgements

This article was researched and written by David O'Farrell specifically for the SCRCA web-portal. Illustrations and photographs by the author, except where otherwise stated.