What are signal boxes?

Railway signal boxes are shelters or small buildings constructed specifically to:

- house the levers and other control equipment used to safely space, route and locally coordinate railway trains; and to

- provide signalling staff with a vantage point from which to safely observe and efficiently control nearby trains.

Why are signal boxes necessary?

The short answer (kindly supplied by Dave Harris) is:

"to maintain a safe separation of trains and to facilitate shunting".

The more detailed answer involves a whistlestop journey through railway history and the key principles of railway operations.

1: Train drivers can't steer their trains

Trains run on (and are steered by) a pair of parallel rails laid on the ground. This means that they cannot steer round one another like road vehicles can. In places where trains need to pass one another (or to change from one route to another), points are installed and these need to be operated carefully to avoid derailments and collisions.

2: Keeping trains safe is harder when things get fast, busy or both

On slow-speed routes with just one train in operation, train crews can stop at points and use an adjacent lever to set the points for the route they want to take. This practice works reasonably well for small-scale industrial railway systems and for shunting in small goods yards, etc. However, for long-distance routes, large industrial complexes and major goods yards, this procedure is highly inefficient. Also, coordinating the trains becomes difficult if more than one train is operating in a given area. Furthermore, as the number and speed of trains increases, so does the risk of a collision.

3: To avoid collisions, rules and procedures are needed

During the early years of railway operations (more than thirty years before the Settle-Carlisle line was constructed), a series of rules and operating procedures were introduced to help things run efficiently (and, with luck, safely). For example:

- Trains theoretically operated to fixed timetables and there was a fixed minimum time interval between trains using the same line. (For the Midland Railway in the 1840s, the minimum time interval was ten minutes.)

- Train drivers were required to maintain a minimum distance from the train in front at all times. (For the Midland Railway in the 1840s, the minimum distance was 800 yards.) Train drivers were also required to adhere to the prescribed timetable.

- A 'pointsman' was stationed at each important set of points to ensure that they were set correctly for each train.

- Policemen were assigned to key locations to enforce the rules regarding train separation and safe operation.

4: To avoid collisions, train drivers need information

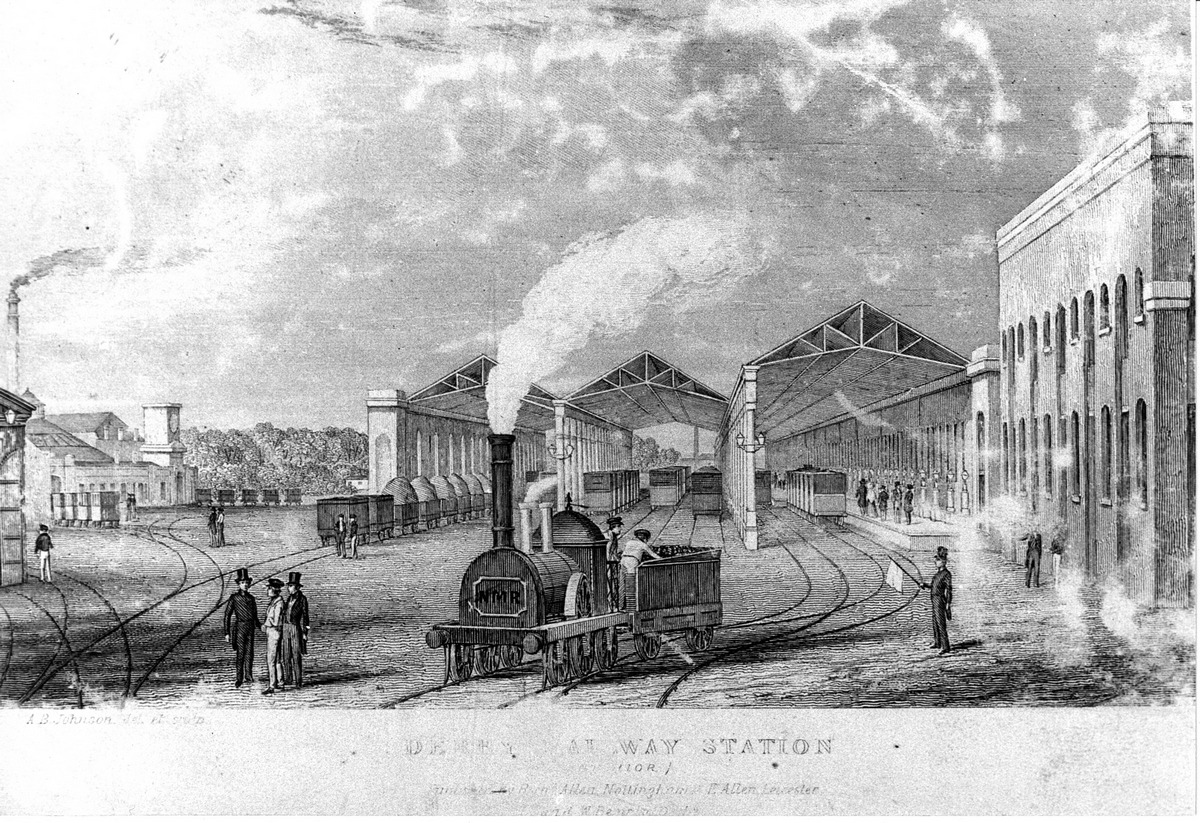

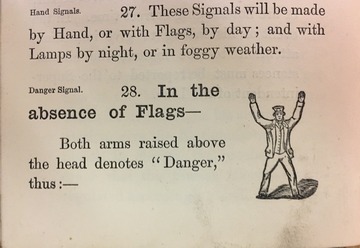

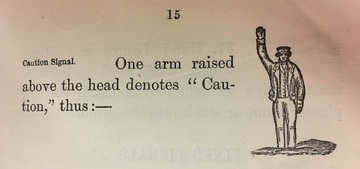

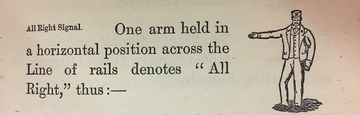

Initially, the railway policemen used hand, flag or lamp signals to tell drivers when to stop and when it was time (and theoretically safe) to depart. This activity is depicted in the engraving of Derby station below, where the man wearing a top hat (bottom-right corner) is holding a flag.

Unfortunately, these early signalling techniques could be difficult to see - or to interpret correctly from a distance - and this caused a number of accidents.

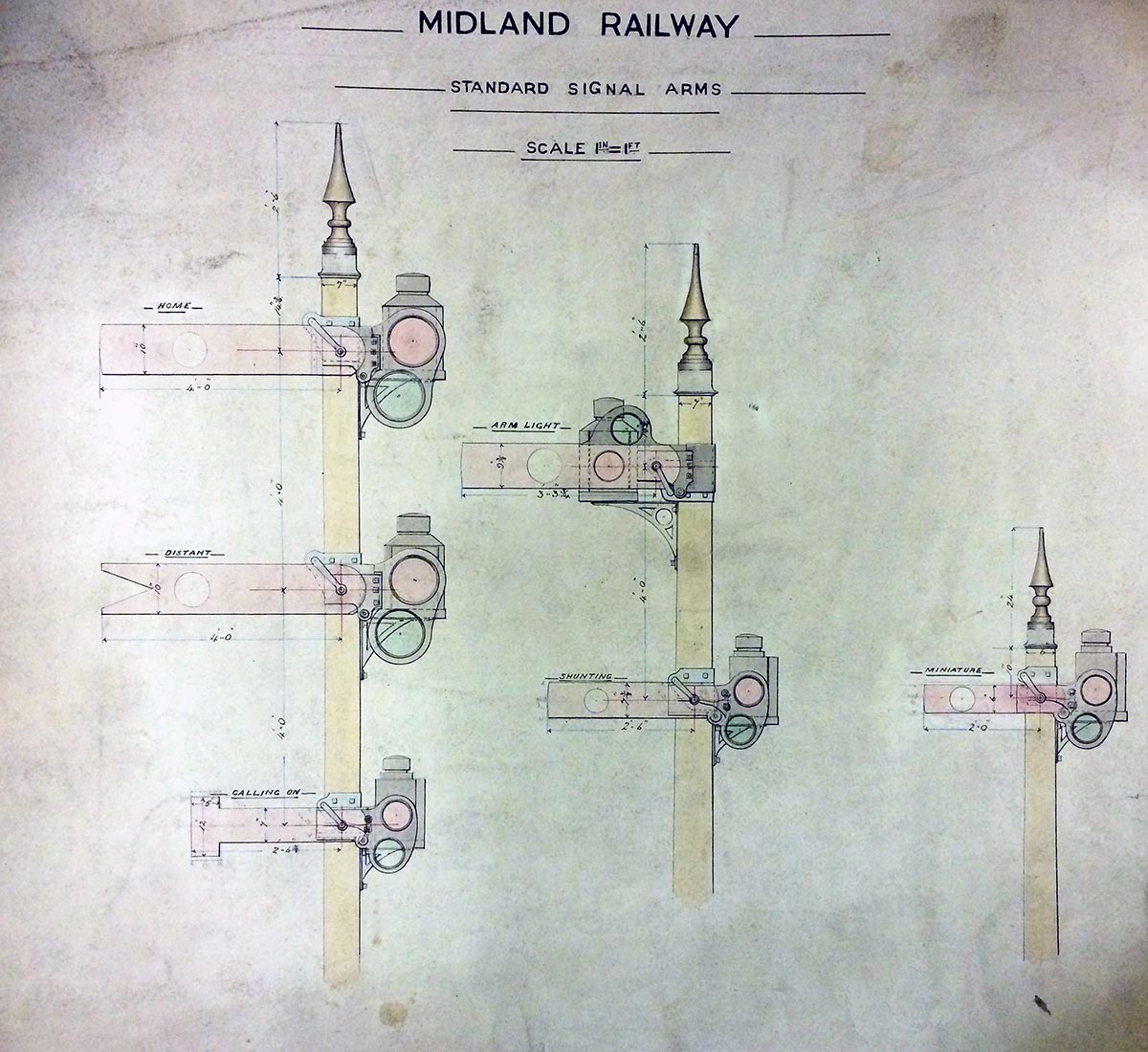

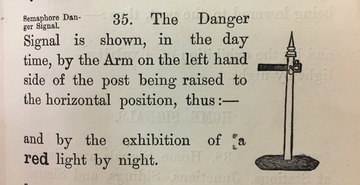

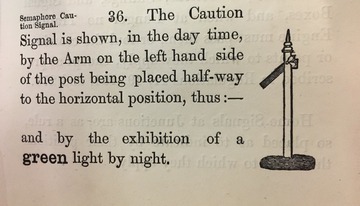

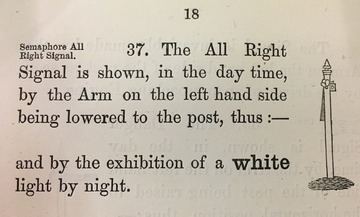

In a bid to overcome this problem, various designs of pole-mounted signal boards were introduced. These were known as 'semaphore signals' and some of the Midland Railway Company's early designs can be seen in the four illustrations below.

In each case, the position of the signal board, ball or arm indicated whether or not it was safe for the train to proceed. Over the years, each railway company developed and refined its own standard design for these semaphore signals (see Figure 1 below).

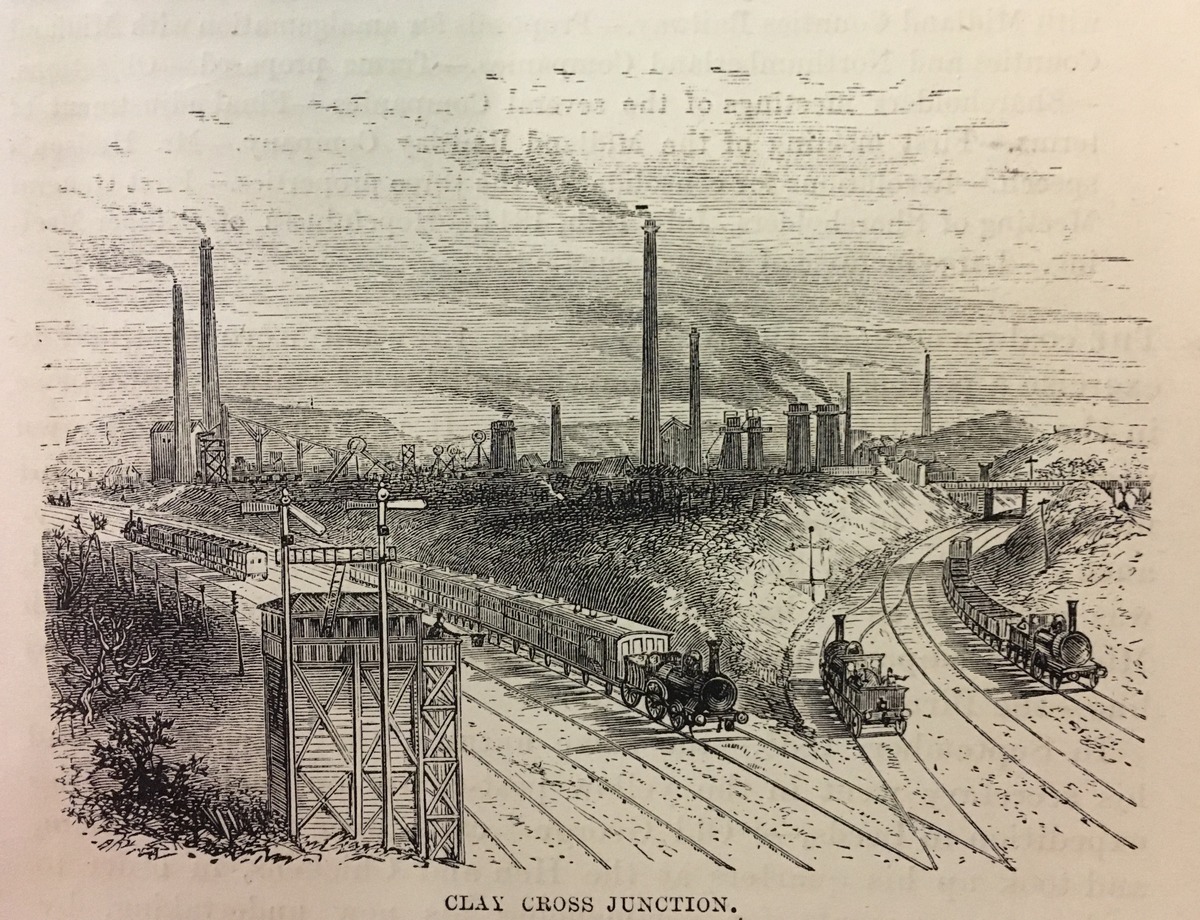

However, there was still a place for hand signals long after the development of post-mounted semaphore signals. This is illustrated in the drawing of Clay Cross Junction above (note the signalman with a flag standing on top of the signalling tower, even though there are two prominent post-mounted semaphore signals next to - and accessible by ladder from - the tower) and in Figures 2 to 7 below.

5: Railway policemen handed over to railway signalmen

In some parts of the railway network, the responsibility for operating the signal boards was gradually transferred to station staff. Eventually, the policemen or station staff performing these 'signalling' duties became known as 'signalmen'.

6: As capacity increased, so did the costs

Initially, pointsmen operated the points via an adjacent lever and signalmen operated the semaphore signals via a lever located at the base of each signal.

As the number of points and signals increased, the number of pointsmen and signalmen also increased. One person was needed for each point or signal and this began to make operating the railways very expensive. It was also very dangerous to have people standing beside the track and there were a number of incidents where pointsmen and signalmen were hit by moving trains.

7: When things get busy, someone needs to take control

At busy locations (such as stations and junctions), it was very difficult to coordinate the operation of points and signals located hundreds of yards apart. A signalman could tell the driver it was safe to proceed before all of the pointsmen had correctly set their points. The solution to this problem was to bring the levers together in a single location, which enabled them to be operated by one person. The railway companies liked this idea because it improved coordination and safety, while also saving money on labour costs.

8: Things (and people) work better when they are kept warm and dry

To protect all this expensive equipment from the weather, it was placed inside small buildings that were specially designed to provide the signalmen with good visibility.

And so the railway signal box was born.

There was another (largely incidental) benefit to these buildings: they gave signalmen somewhere relatively warm and dry to work.

9: Despite all this, people can still make mistakes

Human error is one of the biggest causes of accidents and even carefully selected and well trained people can make mistakes, especially when they are overworked, tired, distracted, overconfident and / or careless. Mistakes by railway signalmen can have particularly devastating consequences and the lessons learned from accidents have resulted in a number of key improvements to both signalling equipment and the associated operating procedures.

During the middle decades of the 19th century, a desire to reduce the scope for human error led to the development and widespread introduction of two of the most important innovations in early railway signalling technology:

- lever frames with mechanical interlocking (to prevent local points and signals being set in a confusing or conflicting manner); and

- the block telegraph system (to improve communication and coordination between adjacent signal boxes).

It is no coincidence that the widespread introduction of railway signal boxes occurred at broadly the same time as the widespread adoption of these two technological innovations.

Unfortunately, despite these improvements, human error could (and still can) lead to horrific accidents. One of the best-known accidents on the Settle-Carlisle Railway occurred in 1910 between Hawes Junction and Ais Gill Summit (see 'The 1910 Hawes Junction Disaster'). Fortunately, lessons learned from railway accidents like this one have led to further improvements in both railway equipment and operating procedures. As a result, travelling by train is now far safer than travelling by road.

The future of signal boxes

In 1948, there were approximately 10,000 signal boxes in Great Britain. By 2012, this had been reduced to less than 500 and the number is falling every year. This dramatic nationwide reduction is the result of the rationalisation of the railway network, developments in electrical / electronic control systems and improvements in communications technology. One of the most visible changes across most of Britain's mainline rail network is the replacement of semaphore signals with coloured light signals. (These are easier to see in the dark and in fog and they can be controlled from much further away.)

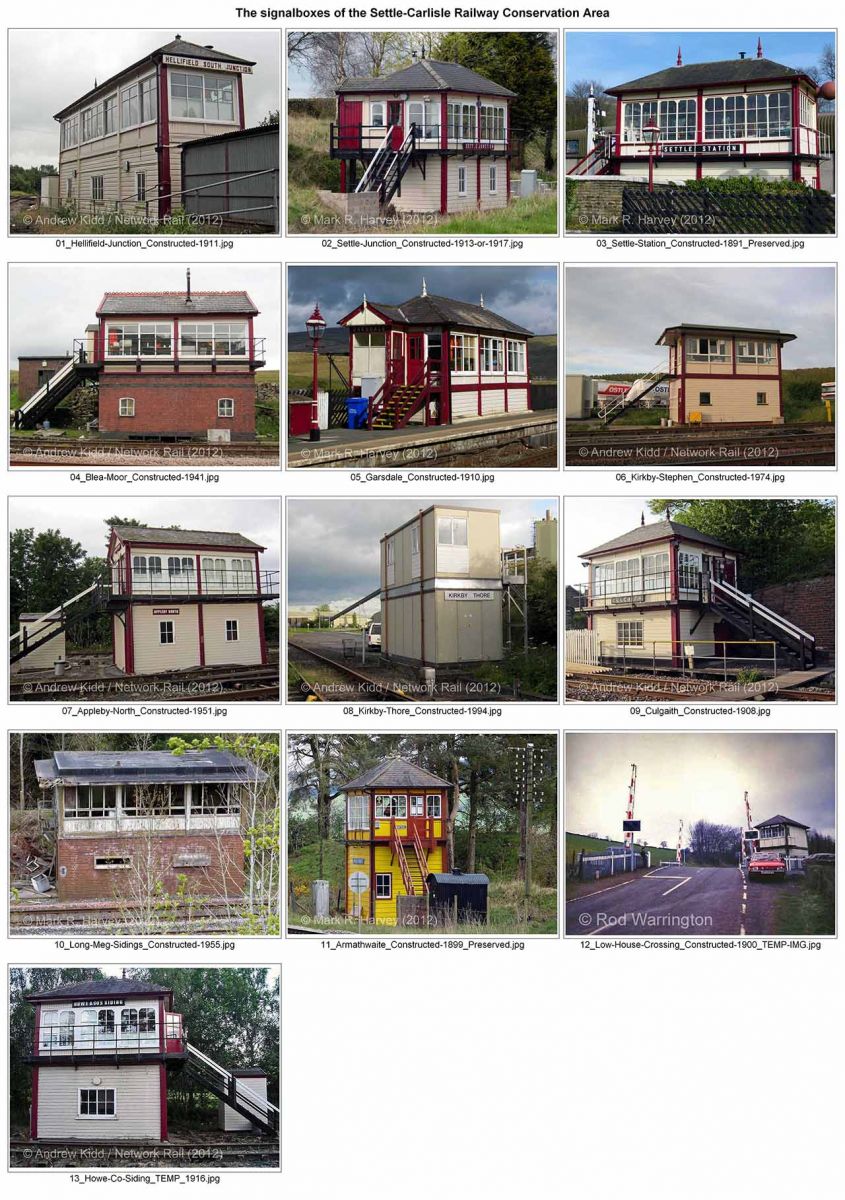

Despite these changes at a national level, there are still nine traditional signal boxes in operational use within the SCRCA (plus one 'powerbox' dating from 1973 and one portacabin installed in 1994). Although this is a significant reduction from the peak of 41 traditional signal boxes, it does mean that most of the railway between Hellifield and Carlisle is still controlled by traditional signalling equipment (see photographs below for examples).

Image 8

Image 10

However, under current plans, the whole of Britain’s national rail network will eventually be controlled from just 14 "rail operating control centres". While the traditional signal boxes within the SCRCA are likely to be among the last to be decommissioned, they will almost certainly become redundant over the next twenty years or so. On a brighter note, two of the line’s signal boxes (Settle Station SB and Armathwaite Station SB) have already been preserved and these now house small museums that are open to the public. The future of the other signal boxes is less certain, but it is hoped that at least one more (Garsdale SB) can be preserved to help tell the fascinating story of signal boxes and signalling within SCRCA.

Further reading

Additional information relating to the nine remaining traditional signal boxes within the SCRCA can be accessed via the following 'virtual visit' page:

https://scrca.aire2eden.uk/virtual-visit?field_location_type_tid=114

The official Board of Trade report into the 1910 Hawes Junction disaster can be viewed and / or downloaded in pdf format via the following link:

https://www.railwaysarchive.co.uk/eventsummary.php?eventID=78

The following online sources provide a wealth of background information relating to the design, manufacture, purpose and operation of signal boxes and the signals that they operate:

- Network Rail's webpage on Britain's signalling heritage:

https://www.networkrail.co.uk/who-we-are/our-history/working-with-railway-heritage/signalling-heritage/ - The 'Derby Signalling' website focusses on the history of mechanical railway signalling in the Derby area:

http://www.derby-signalling.org.uk/- The page entitled "Midland Railway Signalbox types" provides "a very brief introduction to Midland Railway signal boxes and their categorisation":

http://www.derby-signalling.org.uk/MR_types.htm - The page entitled "Midland Signalboxes" contains "a wealth of detail concerning Midland Railway signalling practices and is written by someone who was there":

http://www.derby-signalling.org.uk/Midland.htm

- The page entitled "Midland Railway Signalbox types" provides "a very brief introduction to Midland Railway signal boxes and their categorisation":

- The Signalling Record Society "maintains and shares knowledge of Railway Signalling and Operation in the British Isles and Overseas. Everything from the present day signalling to the earliest times.":

https://www.s-r-s.org.uk/home.php - The Signal Box website "is all about railway signalling. Its primary purpose is to describe the principles behind railway signalling in Great Britain . . . . The emphasis is on the older, mechanical signalling - that worked by mechanical levers and with semaphore signals.":

https://www.signalbox.org/ - The report by John Minnis of English Heritage (now Historic England) entitled "Railway Signal Boxes: A Review" (Research Report Series no. 28-2012). This can be downloaded in pdf format from:

https://historicengland.org.uk/research/results/reports/6071/RailwaySignalBoxes_AReview - David Tyson's memories of Helwith Bridge Signal Box in the late 1950s provides a fascinating insight into the operation of a Settle-Carlisle line signal box.

Footnotes & acknowledgements

[1]: Source: Williams, F.S.: "The Midland railway: its rise and progress. A narrative of modern enterprise" (1876).

Illustrations supplied by Mark R. Harvey and Dave Harris.

Text by Mark R. Harvey (© Mark R. Harvey, 2017).

The author would like to thank Dave Harris for his assistance with this article and for providing many of the images. This article could not have been written without Dave's extensive knowledge of signalling history, practices and procedures.