The village of Culgaith lies approximately six and a half miles to the south east of Penrith and is situated on a hill about 150 feet above the River Eden. It has existed since at least the 11th century[1] and today the population of Culgaith parish is around 850.

On a relatively flat area below the village, adjacent to the river, a suitable deposit of clay for tile[2] and brick making was identified which was free from stones and other impurities. A clay pit was excavated and tile making equipment established so work could begin in 1836[3]. It is believed that a water wheel was used[4] to provide power for the crusher and pugmill[5] prior to the 1870’s when this equipment was offered for sale.

The tiles would mostly be for land drainage use.

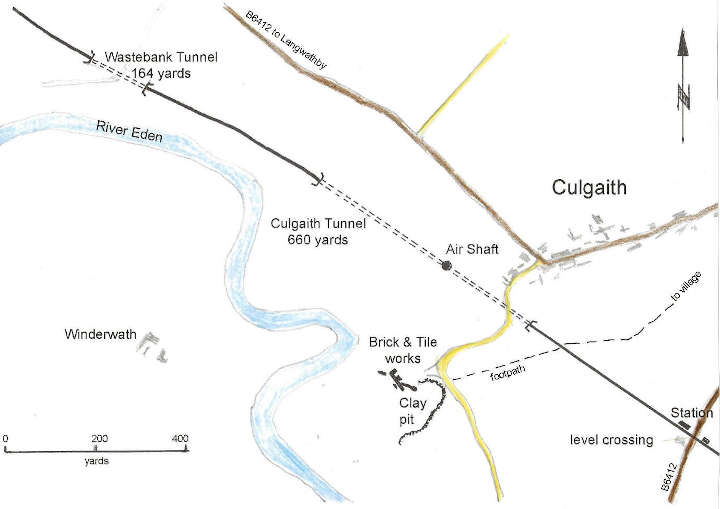

The location of the pit and works is shown in figure 1, which is based on the Second edition Ordnance Survey six inches to one mile map, 1902.

From the 1850’s to 1870 the tilery was owned by Henry Maclean and managed by Joseph Mitchell until the works were put up for sale on Mitchell’s retirement in 1870. They were taken over in 1871 by Messrs. Eckersley and Bayliss, Contractors for the construction of the 24 miles of railway from Crowdundle Viaduct to Petteril Bridge Junction, near Carlisle (Contract 4).

The Settle - Carlisle railway passes between the village and the river, part way up the hill. Initially, it was not planned to have a station at Culgaith but after lobbying by the local residents and landowners, the Midland Railway agreed to provide a station that was opened in 1880. The station was built adjacent to the level crossing and signal box and its architectural style differs from the other stations on the line.

In the Culgaith area there is little space between the meandering river and the higher ground on which the village is located so two tunnels were required to enable the railway to be built. These are Culgaith Tunnel (285 miles 13 chains[6]), 661 yards long and Wastebank Tunnel (285 miles 52 chains[6]), 164 yards long. Culgaith Tunnel was built between 1870 and 1873, Wastebank Tunnel between 1871 and 1873. An embankment was constructed between the two tunnels which necessitated a realignment of the river westwards to create enough space for the base of the embankment[6].

Both tunnels are lined with brick[7] and an access shaft was sunk to assist with the digging of Culgaith Tunnel. This shaft is 74 feet deep[6] and is now used as an air shaft.

The operation of the brickworks during the construction of the railway was referenced by a number of contemporary newspapers and these have been collated recently by Occomore[8].

On 16th July 1870, the Lancaster Gazette reported on the progress of the construction works and that:-

“Approaching Culgaith another length is in progress and immediately under the village, brick making machinery is at work, and, as good material is at hand, a considerable number of the bricks required will be manufactured on the spot”

The Penrith Observer of 8th September 1870 describes the excavation of Culgaith Tunnel and the embankment immediately to the south of it formed from material excavated from the tunnel. It notes:-

“At Culgaith hundreds of “line men” or navvies are engaged informing the monster gullet running through the summit of Pea Hill, which leads to the village. The length of the cutting will be about a quarter of a mile and its depth at the centre of the hill, at which there is a shaft already at work, is about 104 feet. From this shaft there is, night and day, a continuous rising of earth in formation of the tunnel already opened up southwards ... A considerable distance has already been opened out under the direction of Mr Coomb. A brick kiln, a blacksmiths’ shop and a joiners’ shop are attached to the works, as well as labourers cottages, stores, etc. The place is well worth a visit, every facility being afforded of obtaining information.”

The need at this location for a brick lining of a tunnel driven through rock is illustrated by the following item from the Penrith Observer of 7th February 1871:-

“Last week, from some cause at present unexplained, a portion of this immense tunnel fell in. The roof was considered perfectly safe and the workmen were passing regularly. We are glad to learn however, that none of them were injured by the accident”

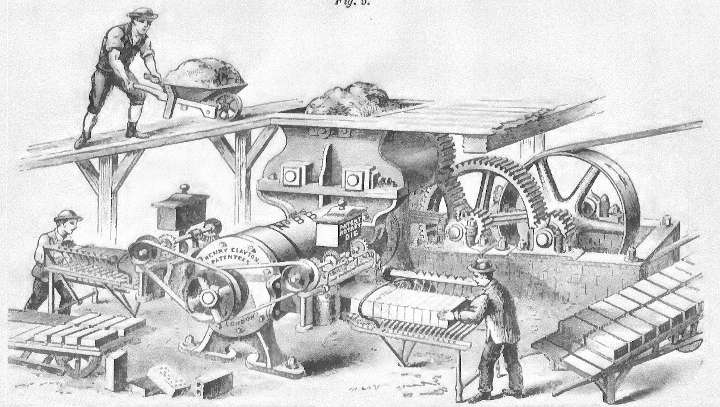

Brickmaking had been partly mechanised during the nineteenth century and a number of companies manufactured equipment. One of these was Henry Clayton of the Atlas Works in London. He had supplied a brick making machine for the extension of St. Pancras Station in 1865 and this type of machine is shown in figure 2 below.

It is described by Dobson[9] who says:-

“It is Clayton and Co.'s second-sized horizontal brick machine, which combines the crushing rollers, pugmill, and brick-forming in one machine. These machines are largely run upon, and have been employed extensively by our great contractors, and upon many public works—facts which give the best assurance that they answer well. One of these machines weighs about 3½ tons, and of this second size, with about 8 or 10 horse power, will turn out from 75,000 to 90,000 bricks per week.”

The power to drive the brick making machine was most likely provided by a stationary steam engine.

It is quite possible that this type of machine was in use at Culgaith from 1871. In his book, Occomore notes that Mr John Bayliss (the Contractor) purchased a brick making machine in June 1872 from Porter and Co. in Carlisle, but it isn’t clear where this was to be used since Eckersley and Bayliss were also operating the Cumwhinton Brick and Tile works at the time (see Brick works in the Cotehill area). Porter and Co. had also supplied brick making machines to the Batty Green brickworks which was supplying bricks for Ribblehead Viaduct (see Ribblehead Railway Construction Camp: Brickworks).

During Victorian times workplaces were often very hazardous as the following extract from the Penrith Herald of 29th November 1873 illustrates.

“Culgaith - On Saturday last a boy named Edward Fitzpatrick, eleven years of age, met with an accident which resulted in his death. He was employed at the brick works in connection with the Settle and Carlisle Railway extension and whilst oiling the machinery he made a remark to another boy engaged upon the work. His companion threw a piece of clay at him and in stepping to one side to avoid it, he stepped too close to the machinery, by which he was caught and dragged in amongst the wheels. His loud shrieks speedily brought assistance; the machinery was stopped but not until his body had been mutilated in a shocking manner. Surgical aid was procured, but it was of no avail, the injuries internally and externally which he had received being so extensive that he succumbed to their effects at six o’ clock the same evening.

At the Inquest, which was held on Monday before Mr J Carrick deputy Coroner, it transpired that the boy had every half hour to pass around the machinery and in one place only 21 inches space intervened between the embankment and the engine. This the jury considered extremely dangerous and Mr Bayliss jun., the son of the Contractor, who was present, promised that in future the machinery should be properly fenced off and persons attending to it protected from similar casualty. The jury recorded a verdict of accidental death.”

The tunnels were completed in 1873 and Mitchell[10] notes that the Lancaster Guardian published the following description-

"At Culgaith….there is a tunnel through a high bank in a forward state towards completion. It is 800 yards[11] in length, 700 yards of which are completed….the sides and arches are of brick. The facings at the entrances of the tunnel are of blue Staffordshire brick with string courses and coping of freestone. The excavation was through hard red marl."

It appears from this that the use of the Culgaith bricks was confined to less exposed locations such as the multiple layers of the tunnel lining. Staffordshire Blue bricks are known for being hard and very durable and would be more resistant to the weather conditions. They would also appear more decorative.

One of the original means of access to the works for the workers was by a footpath which ran from the east end of the village. This provided a much less steep way back into the village compared with the road to the west end of the village (known locally as “The Pea”) which is very steep. The path was severed by the construction of the railway, so a foot crossing was provided at 284m 75ch, between the station and the tunnel. This crossing was later referred to as “Culgaith Tile crossing”[12].

In 1873 the works were offered for sale and bought by Edward Brown who operated the works until his death in 1877 at the age of 48, when his widow, Sarah continued operations until 1884 when the works were again sold.

This time the works were bought by two Misses Wilson of Penrith who in 1885 appointed Samuel Taylor as manager. Taylor had gained wide experience in many Cumbrian tileries and he managed it until his death in 1906. Four of his sons worked at the tilery and on his death, two of them took over. They made some bricks but mostly drain tiles until 1926 when a local farmer, Joseph Stamper, bought the works.

Stamper invested in updating the works and in 1926 installed a ship’s boiler to provide steam for heat to dry the bricks and tiles. He also built a chimney 90 feet high for the boiler which was topped out by his daughter Margaret[13]. The economic depression of the 1930’s affected the brickworks badly and caused Stamper to lose a considerable amount of money. Partly to offset this, one of his sons, John and his daughter, Margaret set up a haulage business, J G Stamper, in 1934 based at the brickworks. They hauled materials for McGhees, the Gypsum producers at Kirkby Thore and for West Cumberland Farmers delivering farm supplies.

In 1938, Joseph sold the brickworks business to a Mr Baines, a builder. He initially made bricks then turned to making concrete products until the beginning of the war. During the Second World War, the sheds of the brickworks were used by the Government for storage of materials such as wire and diesel engines.

Production of Concrete products resumed after the war and continued until 1957 when the Culgaith Engineering Company was formed with Mr Baines as a Director. This company manufactured caravans and employed around 36 people. It is not known when this business closed but it is likely to be before 1980 when the site had reverted to being a haulage depot for J G Stamper.

In 1981 work was carried out to provide a new haulage depot on the site and the old brickworks chimney was demolished to make space[14].

At the time of writing (January 2022), the site is no longer used by the haulage business and the sheds are used by a company which provides temporary structures for outdoor events and festivals. Elsewhere on the site there is a reclamation yard and a vehicle repairer. A public footpath runs along the north east boundary of the site.

Footnotes & Further Reading

[1] Huddart, Ada - The Story of Culgaith and its People (1959)

[2] In the Oxford English Dictionary a tile is defined as a thin slab of burnt clay, shaped according to the purpose for which it is required – semi cylindrical or tunnel shaped when used for drainage or a variety of shapes when used for roofing.

[3] Solway Past – History in the Borders – Cumberland Brickworks http://www.solwaypast.co.uk/index.php/bricks/14-brick/82-cb

[4] E. & S.B. Davis – Draining the Cumbrian Landscape (Cumberland & Westmorland Antiquarian & Archaeological Society, 2013 ISBN 978 1 873124 63 5)

[5] A pugmill is a machine for cutting and mixing clay with water to the correct consistency. These were sometimes horse powered.

[6*] Measured to the centre of the tunnel. Williams F S -The Midland Railway: Its Rise and Progress (1876 - reprinted by David & Charles,1968 ISBN 0 7153 4253 3)

[7] V R Anderson & G K Fox – Stations and Structures of the Settle – Carlisle Railway (Oxford Publishing Company, 2nd edition 2014 ISBN 978 0 86093 662 6)

[8] Occomore D – The New Railway to Scotland – The story of building the Settle to Carlisle railway from newspapers of the time 2020 – Hayloft Publishing ISBN 978-1-910237-43-4

[9] Dobson E – The Practical Brick and Tile book. Eighth edition 1886 (Crosby Lockwood and Co. London)

[10] Mitchell W R -How they built the Settle-Carlisle Railway- Castleberg 2001 – ISBN 1 871064 03 1

[11] The tunnel is actually 660 yards long

[12] S&C Resources Directory -- Appendix 5 - All bridges and line-side features

[13] Obituary for Margaret Stamper – Cumberland & Westmorland Herald, Penrith – 3rd August 2002

[14] 25 Years ago – Culgaith - Cumberland & Westmorland Herald, Penrith – 8th July 2006

Acknowledgements

This article was researched and written by David O'Farrell specifically for the SCRCA web-portal. Illustrations and photographs by the author, except where otherwise stated.